|

Since 2010 I've supervised MSc students in their fourth and final semester, where they design, research, write, and defend a Master's Thesis in Sustainability Science. Tomorrow I'll meet my new batch of students for the first time, and we'll make a plan for working together in the coming semester.

First meeting agenda:

Helpful resources for your thesis research: Here are guides I've written over the years that I hope can help you get started or make the thesis process a bit less overwhelming. Research design

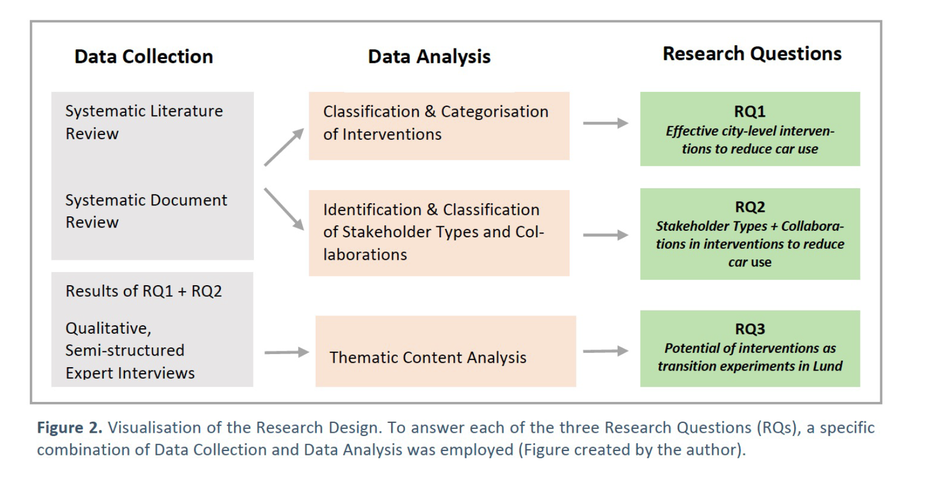

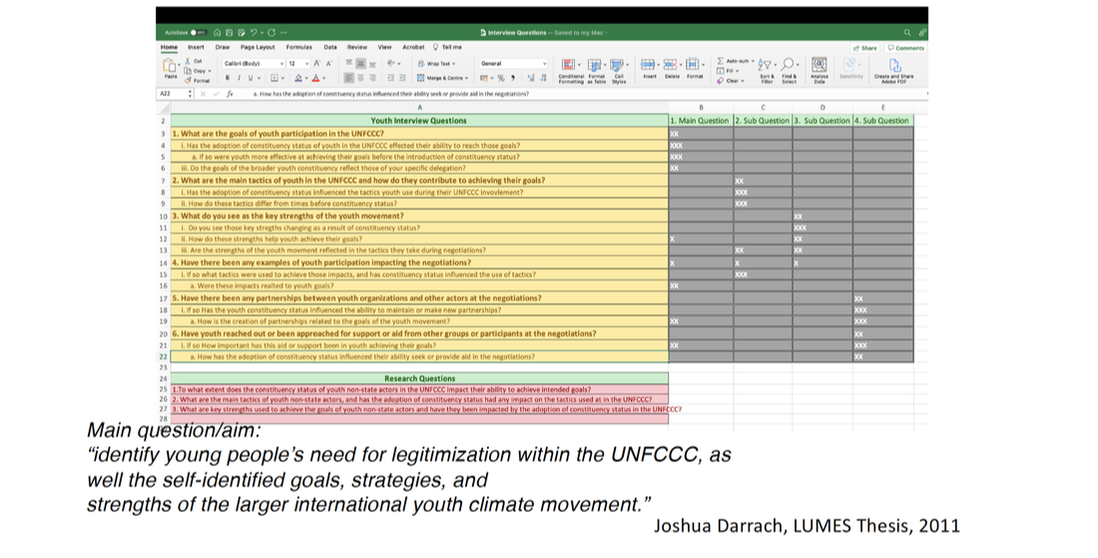

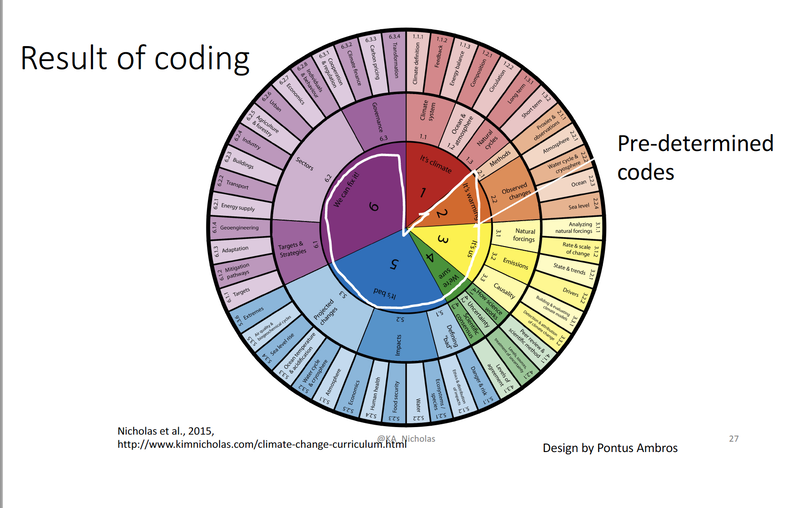

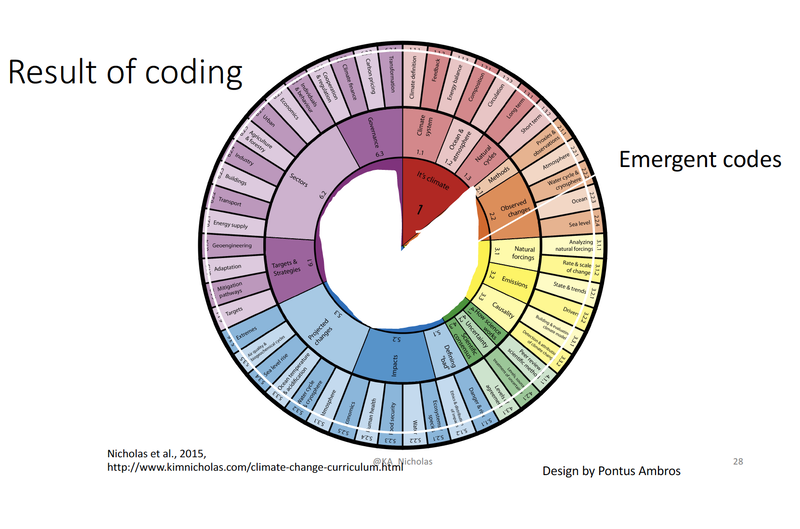

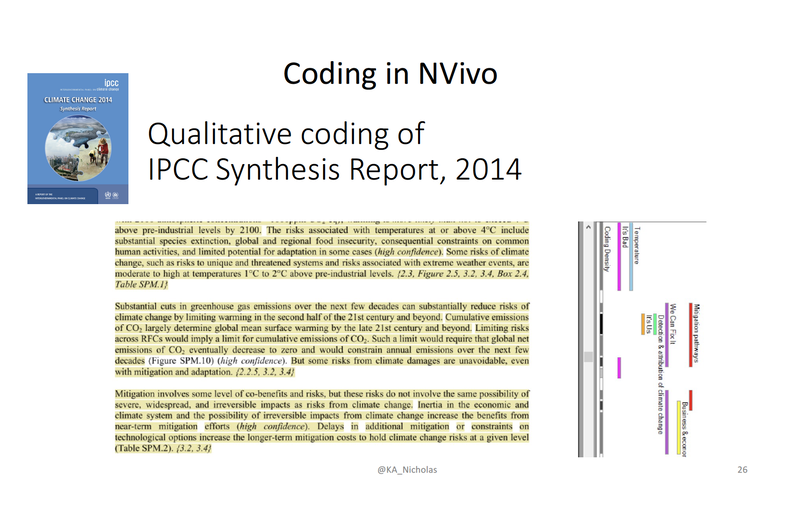

Good luck, thesis writers! You can do it! 1. Align RQs + methodsAlign your research questions with the methods you will use to collect and analyze data to answer those questions, like Paula Kuss did for her 2021 LUMES thesis. 2. Align RQs + interview questionsMake a table aligning the questions you plan to ask in interviews with your thesis research questions. This will show how the answers to interview questions will add up to answering your thesis research question. Here's an example from Josh Darrach, LUMES thesis 2011. 3. Plan for coding qualitative data in NVivoInterviews generate text, which can be transcribed from recordings (plan for 4 hours transcription per 1 hr interview; consider automated alternatives). A practical option is to take detailed field notes immediately after your interview (book time between interviews to do this), and work with those initially, supplementing with recordings. Qualitative data can also include text or images from existing documents. You'll need a program like NVivo for qualitative analysis. Here's an example of using NVivo to code the 2014 IPCC Synthesis Report (Nicholas et al., 2015). Some of the codes were applied from existing categories, while others emerged from the coding process. The final codes are represented in the rainbow wheel below. Further readingHere are my lecture slides for the LUMES methodology course on designing and carrying out interview research and on analyzing qualitative data, with lots of practical examples.

You finished your thesis! Congrats!! Please make sure you've celebrated and slept well since you finished-- you deserve it.

Then, keep reading! Are you back? Good, because if you want the world to benefit from all your hard work and new discoveries from the last six months of blood, sweat, and tears, you're not done! The people who can benefit from what you found need to hear about it in a way that answers their questions or solves their problems. (Hint: that format is very, very rarely a 12,000 word master's thesis.) At a bare minimum, you should email a copy of your final thesis to everyone who helped you in your research, including research participants, and thank them. Do this now, before you leave for summer. To increase the chances that people can benefit from your work:

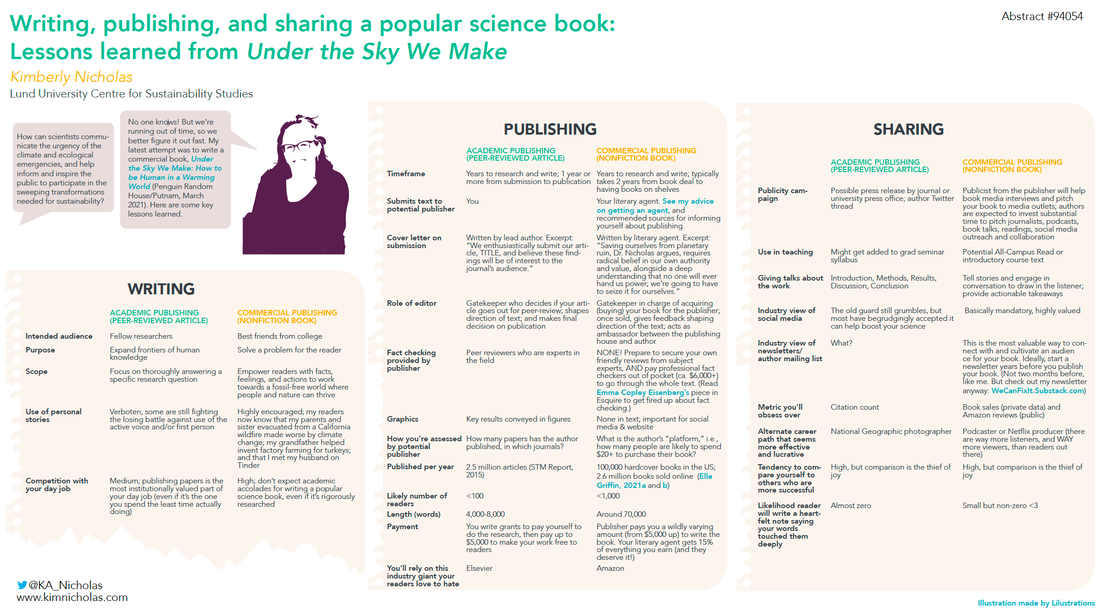

Good luck and thank you for asking and answering research questions, the world needs what you found! Everything I needed to know about putting a commercial book out in the world, I learned from 20 years in academia... not!

Here's my guide to navigating the differences in norms and expectations between the worlds of scholarly articles and commercial books. Feel free to reuse with attribution. Click on the image below to download the full-resolution PDF with live links. Originally presented at the Ecological Society of America annual meeting, August 2021. Thanks to Emma Li Johansson of Lilustrations for design. Good luck writing! I just hosted a publishing workshop for our PhD students, discussing common questions around the academic publishing process. Here I want to share some of our key takeaways about how to select a journal, as well as compile advice and resources I've written over the years about writing, (co)authorship, and peer reviews. I hope this helps demystify some of the academic publication process. Good luck! How to select a journal

How long from submission to publication?

How do I...?

P.S. Free, unsolicited academic and life advice! Recommended reading

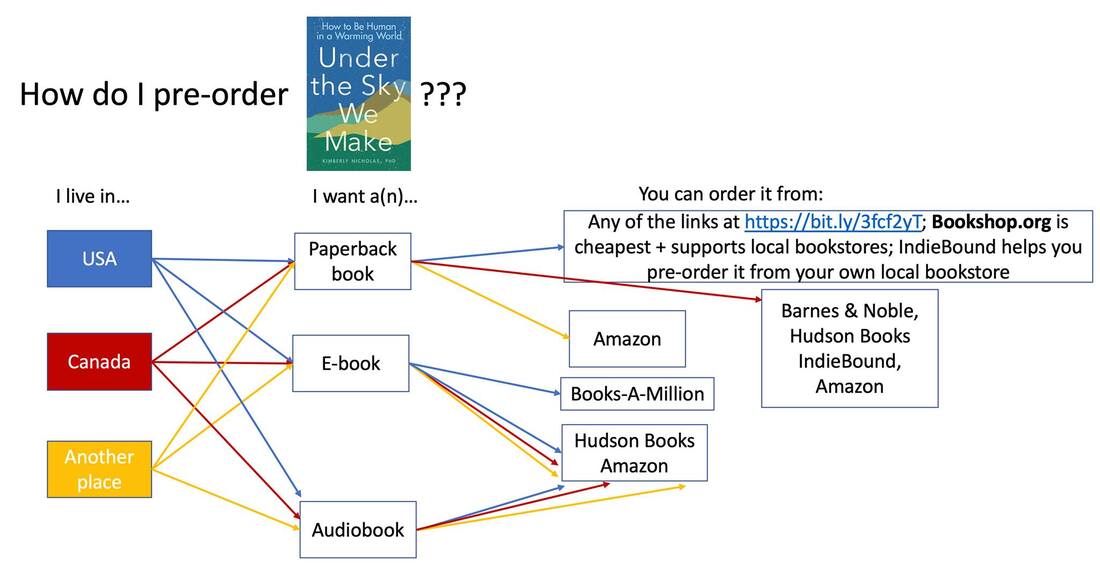

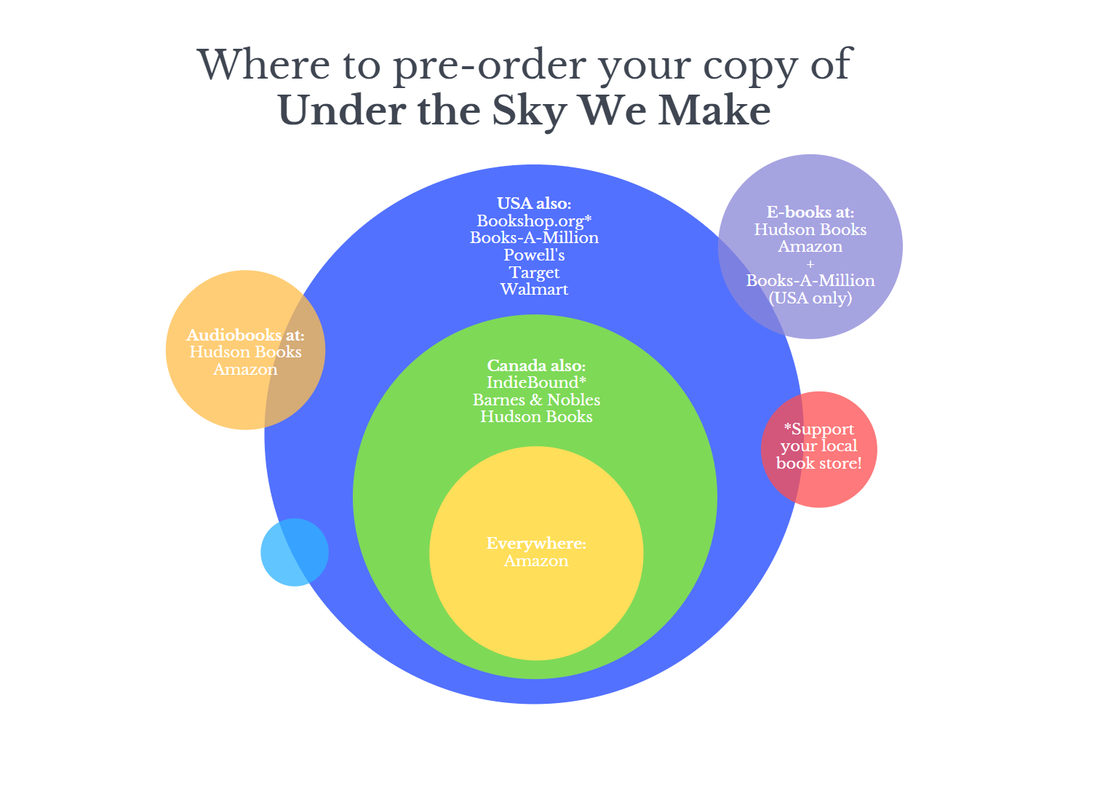

Hi friends! I'm SO happy and grateful that many of you want to read my new book- thank you!! So where can you get your hands on this wonderful book?? Well, by clicking on these buttons; or reading on for more details! US and Canada: Everywhere!Long story short: my current book deal includes a contract for distribution in North America (US and Canada). In those two countries, the book is widely distributed by Penguin Random House, including to independent local bookstores (you already know where your local bookstore is, right?? If not, you can check IndieBound to find your local shop). Here are all the available ordering sites (even though now we're past pre-ordering) from PRH USA or Canada. Here's a more aesthetically pleasing version contributed by my former student Fabian Bendisch! Outside US/Canada: It Depends!Outside of the US and Canada, it's still possible in most places to buy my book! But it's a bit trickier. TLDR: The easiest place to find my book online is Amazon, which has all three formats (paperback, e-book, and audiobook) available in most of its markets. This link should take you to your country's Amazon page for Under the Sky We Make. Another widely available international option is Book Depository (which is owned by Amazon). These large retailers order more books and therefore have them more widely distributed and longer ahead of time. If you want to order from a national online bookstore in your country, please check this link for options that other readers have told me about. If you want to order from a local bookstore, this happens on a store-by-store basis. Please see the reader-contributed list below. If you don't find online options here for your country, or independent bookstores at the end of this post, please call your local bookstore and ask them to order it for you (here's the info you need). Thank you! Where to order in SwedenHere's where I've found you can order UNDER THE SKY WE MAKE online in Sweden: Paperback book (181-239kr): Adlibris, Akademibokhandeln, Bokus (use code SKYWEMAKE for 20kr discount) e-book (215kr): Adlibris, Bokus, Google Play Audiobook (129-: Audible, Google Play (129kr) +Amazon has all 3! Indie bookstores that can order Under the Sky We MakeThanks to readers for letting me know where you got your copy, so I can share. Call or email these lovely people to get your hands on a copy today!

Country-level bookstore guidesThese aggregator sites give options for buying the book online, with price and delivery comparisons for a given country, and/or guides to finding your local bookstores. Thanks to readers for submitting!

Will there be a German/ Mandarin/ Spanish... edition?As a first-time author, getting international distribution beyond North America basically depends on book sales of the North American edition. More sales = more likelihood of international contracts and translations! So if you want to help support UNDER THE SKY WE MAKE, and give it the best possible chance of being picked up for international distribution and translation into other languages, please support the current, English-lanugage edition:

Why is it like this, and what can you do about it?TLDR: Book distribution is hard; to support the book, please buy the current edition wherever you can, tell friends to do the same, and tell me where you bought it, so I can make it easier for others to find. Thanks! More deets:

The North American edition is the only one that exists right now. It gets distributed by third party exporters from Penguin Random House in the US to international markets. But I have no control over where it is or isn't available. (Here ends my knowledge about international book distribution rights.) I realize I'm very lucky to have a commercial book deal in North America. Despite efforts by me and my agent, though, I don't have a contract outside this market. It's frustrating for me and for readers that it's harder to find my book outside the US and Canada. It's also a challenge that, in this online age, many independent bookstores outside North America who *can* get my book don't have it on their website. You have to call or email them and they will order it one copy at a time. There may be delays of a few weeks for shipping. But it's possible! And this is what *you* need to do if you're committed to supporting local bookstores! :) Here's where I need your help, dear reader, to find where UNDER THE SKY WE MAKE is available in your country! You know where your closest bookstore is located in your town, and where to order books online in your country. And if not, you know how to Google "buy Under the Sky We Make" in your local language from your country-based IP address. Then you can buy from their website (where that's an option), or call or email them where it's not. I don't know any of those things, certainly not for your town, and there is no central directory of independent bookstores, or even of major chain book retailers by country (AFAIK, please tell me if there is!). Thanks to help from others, I've assembled the list above. Please add in the comments or write me on social/at the email link below if you find a new source in your country, and I'll add it here. Thanks for your patience, sorry for the hassle, and please keep reading and spreading the climate action love! xo Kim Hello comrade in writing arms! Welcome to the weird and wonderful world of book publishing!

I have lots of thoughts about the writing itself, but in this post, I will focus on the practicalities of getting a book *published* rather than written. That is, how do the words you write get made into a book that will sit on a shelf, calling out to a reader? (The part about how you get a reader to know your book exists and want to read it is called book marketing- here's a good podcast about that for when you get there!) Here are some things I wish I'd known when I was starting this whole process. (Or maybe I wouldn't have wanted to know, as it looks pretty darn intimidating when I spell it all out- but I hope that knowledge is power and you find this helpful!) How did you get your book published? I started working on my first book, UNDER THE SKY WE MAKE, in July 2017. I would write for half an hour before work most mornings. I found my fierce literary agent Anna Sproul-Latimer in July 2019 (via my bestie Lucy Kalanithi- thank you Lucy!!). Anna sold my book proposal to my wonderful editor Michelle Howry at Putnam (a Penguin Random House imprint) in February 2020. I submitted the full manuscript in May 2020, did tons of editing and fact-checking over summer and fall 2020, and the book will be published March 23, 2021. This is an example of "traditional" (sometimes also called "trade" or "commercial") publishing; see below. Believe it or not, this timeline is considered very fast in the publishing world! (At least, the time from when I found an agent to when the book will be on shelves and e-readers and in earbuds. I was very lucky to be supported by a team who believed in the book and wanted to help get it out in the world. Probably the fact that I had written like 200,000 words when I met Anna helped, though that also created other problems too!) How do I publish a book? Well, there's the writing part, which I won't cover here- but you need an idea that you’re excited to write around 70,000 words about (give or take a lot). And then rewrite. And rewrite. And fact-check. Repeat, etc. There are two kinds of publishing: traditional publishing and self-publishing. Traditional publishing in the United States (the largest book market globally, with almost a third of sales) requires that you find a literary agent, who will coach you in developing a book proposal which they will submit on your behalf to a bunch of publishers. (The major US publishers do not accept submissions directly from authors; agents have the contacts and knowledge for where to pitch your book for the best chance of success.) Hopefully one or more of the publishing houses your agent sends your book proposal to wants to give you a book deal, i.e., pay you to write the book you describe in the proposal. In traditional publishing, once the publishing house gives you a deal, you will work with professional editors, copyeditors, publicists, and other publishing professionals to help edit, publish, design, distribute, and market your book. Traditional publishing is full of lovely people who are passionate about books; it is also a business. Publishers are looking to publish books they think they will make money from, i.e., where there is a substantial commercial audience (group of people ready to shell out $15-$30 in cold hard cash for the chance to read or listen to your words). You have an idea you want to get out into the world; they want to sell books. Everyone wins if you sell a lot of books! (However, this is rare, and difficult. See below.) Self-publishing means you as the author are in charge of every step from writing, editing, copyediting, publishing, marketing and distribution (or you are in charge of finding people to do the steps you don't do yourself). How do I self-publish a book? Sorry, I don’t know anything about this! There are pros and cons to traditional vs. self-publishing, and people on The Internet have lots of thoughts about them! If you find some particularly helpful resources, please share them with me and I’ll link them here. How do I publish a non-nonfiction book, that is, fiction or something else? (Side note, isn't it weird that "fiction" is the baseline norm of books, and you must specify "non" if you fall outside that genre? Why isn't it "truth" and "non-truth"? Or "real stuff" and "things I made up"? But I digress.) I'm not sure, I don't write fiction! I think for example a book proposal for fiction looks very different than my nonfiction one I describe below. Please do your homework! How do I find a literary agent? This is a very intimidating step and I procrastinated about it for a long time!! Hence two years elapsed between when I started writing my book and when I found Anna. In hindsight I would have saved us both a lot of time if I'd started my search for an agent sooner (although then maybe Anna and I never would have met, sliding doors yadda yadda). You need an agent if you want to traditionally publish a book. Literary agents, and the entire publishing industry, are shrouded in mystery to the novice, or at least that’s how I felt. The most comprehensive way I found to get an overview of active and reputable literary agents in the United States is to pay $25/month for an account on Publishers Marketplace. With its charmingly functional design straight out of 1997, this is the publishing industry clearinghouse where you can look up agents and see their stats- what genres they represent, how many books they’ve sold, etc. You can also see which agent represents your favorite authors, and represents authors with similar books to the one you want to write (“comp titles”). When am I ready to get an agent? I would say you need to have done some substantial thinking, writing, and editing on your book idea, so that you are prepared to share: - an elevator pitch for the argument of your book. (Note, clarifying the argument is the hardest part and a good agent will help you revise/improve it, but I think they will be impressed if you can write the sentence, "In MY BOOK TITLE I argue that X." - an outline of the chapters you plan to write (like a table of contents) and at least some ideas about what goes in each chapter and how they relate to each other. - a reasonably strong draft of at least one full chapter, i.e., writing you would be OK with a stranger reading and judging you on. - a compelling argument for why this book is needed in the world (by whom? Who are the readers you are trying to serve?), and why you are the one to write it (establish your credibility). How do I get a literary agent to represent me? You’ll need to query them, i.e., send them an email introducing yourself and your book idea in a compelling way that makes them want to represent you, and ask if they are accepting new clients. Some agents are “closed to queries,” in which case you should not annoy them by sending them a query anyway. Read and follow the query guidelines on their website. Some agents will want just a cover letter, some will ask for a sample chapter, or a draft book proposal. Agents are notoriously overbooked, so it will likely take some time for you to hear back from them, and many of them will say no. That sucks, but take heart. It's like dating- you don't need everyone to like you, you just need to find the one person you click with. What does a nonfiction book proposal to a traditional publisher look like? In my case, it was a 20,000 word document that I labored on with my agent for eight months before we sent it out (after I had already been working on the book itself for nearly two years). My proposal contains a 3-page overview of what the book is about and why it’s needed (establishing the market, i.e., the publisher wants to know that there is a large group of people who are likely to be interested in buying this book), a 3-page “about the author” where I try to sound very fancy (this is to establish my authority of the subject, my credentials as an expert, and importantly, my “platform”, which is publishing industry code for “how many people are fans of yours who will buy a book that you write?” This is a cringe-worthy section to write about yourself, thank goodness for agents who are great at it). The remaining 60-ish pages are chapter outlines. These establish the basic structure of the book, as well as what goes where. Each chapter has an overview (a ca. 1 page summary of what the chapter will argue) and almost all chapters have substantial content, e.g., a 3-8 page sample excerpt of text that would appear in the final book. What does an editor at a traditional publishing house do? Given the title, I rather understandably thought that an editor's job was mostly to edit text, that is, to read and discuss and comment on words on a page and offer constructive feedback for how to make them shorter/punchier/better. An editor does this! But they also do a lot more. The editor is the one to "acquire" your book for the publishing house. The editor will read your book proposal and decide if it's a project they want to undertake, in which case they'll share it with colleagues and ultimately get approval from the "publisher" to bid on it. (In this case, the publisher is not the company/publishing house that appears on the spine of the book like Penguin, etc., but rather a senior executive-type person who sets the editorial direction of the publishing house, and ultimately controls the purse strings. Confusing, I know!) Throughout the publishing process, your editor will be acting as an "ambassador" of the publishing house. They will introduce you as needed to some of their colleagues working on various parts of the book, who you'll work directly with (like publicists and marketers), and sometimes the editor will act as an intermediary between others, like copyeditors, designers, proofreaders, and others who you might not meet directly. The editor is your main point of contact with everything happening at the publishing house. How do I publish a book outside North America? Sorry, I don’t have any experience with this! My current book contract is for distribution in North America (which includes the US and Canada, and also the Philippines for unknown-to-me Publishing Reasons). I hope publishers in other countries will want to buy rights to distribute my book in English in their country, and translate it to local languages, but this hasn't happened for me yet (my agent is working on it). At the moment, to buy my book outside North America, booksellers are jumping through some hoops (here ends my knowledge of exactly what they’re doing, but I can say that my book seems to be available for pre-order (what's pre-order and who cares?) nearly everywhere in the world on the largest online book retailer whose name rhymes with Autobahn, and through many independent bookstores, though often only after publication). If you are based outside the US and Canada, and/or your market (target readers) is outside the US and Canada, I would guess you should look for an agent in your current country, which I don’t know how to do, beyond Googling "name of author you like" + "agent" (thanks to Alice Bell for this suggestion!). What’s the difference between academic publishing and trade publishing? I have not published an academic book. But my understanding is that it looks very different than what I’m describing here. As an expert in an academic field, you write a proposal directly to an academic publisher, and eventually sign a contract with the publisher (no agent is involved). I have heard these proposals are much shorter and simpler than the 20,000 word proposals you need to get a traditional book deal, perhaps as little as a few pages. One important difference is that (as far as I understand) you will not get paid to write an academic book (no “advance”), support from the publisher in editing and promotion are likely to be lower than in traditional/trade/commercial publishing, and the market is primarily (though not exclusively) targeted at academics (scholars within your subject). How does the money work? Ugh, how crass, money. Well, we live in capitalism (for now) and have to pay rent, so let's talk about it! Before we do, though: for your sanity, it's important to think about why you want to write your book, and how you want your book to fit into your broader mission on Earth. No single book is the be-all, end-all, but you want to believe in your book enough to invest years of your life into it, and do it in such a way that you'll feel you did your best, regardless of how the money shakes out. Speaking of money: If your goal is to be rich, don’t write a book. It's hard to find real numbers on this, but I keep reading that most of all books published sell fewer than 1,000 copies. Even most traditionally published trade books from a major publisher (where substantial resources are invested in paying the author an advance, paying for the time of professional editors, copyeditors, publicists, etc.) sell far fewer than 10,000 copies. Womp-womp! Your contract will specify the exact terms (and your agent will be the one to negotiate them for you and explain what they mean and what is reasonable- a very important job!). From what I understand, it’s common for a commercial book deal to consist of an advance (money the author makes before the book is published, for the work of writing the book) as well as royalties (money the author makes if the book “earns out”, that is, you sell enough books that the publisher recoups the costs they have spent on it, often set around 10,000 copies). Data on author advances are not public, though the announcements on Publishers Marketplace sometimes use a cute code where "nice deal" is below $50,000, "very nice" is $50-99k, "good deal" is $100+ and there are finer distinctions after that, but TBH as a first time author, this will probably not be your problem (unless you're already uber mega Obama-level famous, in which case, could you please do me a favor while you're here, and Tweet about my book? Thanks!) My anecdotal understanding is that Big 5 traditional publishers offer advances starting somewhere in the range of $30,000-$60,000, with smaller independent publishers likely have smaller advances. However, this blog post by agent Chip McGregor says (after lots of prevaricating) that an average first book deal might be $5k-$15k for fiction and $5-$20k for nonfiction. I honestly have no idea what to expect across the industry. Ask your agent, and don't quit your day job. (Or, throw yourself into author-entrepreneur mode, and embrace the hustle!) Book advances are paid in installments (for example, 1/3 upon signing the contract, 1/3 upon delivering a full manuscript, and 1/3 upon publication). If you deliver the book you promised to the publisher's satisfaction within the terms of your contract, you will get paid your advance (that is, it doesn't depend on how well the book sells, or not). Note that your agent gets a flat fee (industry standard is 15%) of all the money you make as an author (and they are worth every penny). A reputable agent should never ask an author for money upfront. An agent is investing in you as a client because they believe in your work. They are accepting the risk that they will never make any money from you (if you don't sell a book), and certainly will not make any money from you for somewhere between a little while to a looooong time (until you sell your first book). I’ve read that 95% of books do not “earn out," thus very few authors ever earn royalties. Here’s more info on the financial side. Note that you should find a qualified accountant to help you manage and report the money correctly for taxes, and probably you will want to set up a business (e.g., a limited liability corporation or sole trader) for when you do get a contract. Huzzah! How can I learn more about book publishing? This is all so confusing and intimidating. I know! Sorry about that. Don’t give up- the world needs your book! Here are some resources I’ve found helpful. Part of me wishes I'd started reading publishing industry stuff years ago, to help me prepare for my impending book launch, and part of me is glad I didn't, so I focused on writing the book I wanted to write (but now I feel behind on a lot of the industry knowledge). Wherever you're starting from, you are not alone! How to Glow in the Dark- this is a weekly newsletter about all aspects of book publishing, written by my brilliant agent, Anna Sproul-Latimer, to demystify the process with expertise and empathy and humor. It is well worth the subscription price. Agents and Books- I subscribe to Kate McKean’s newsletter and find it very helpful. I’ve sent in questions to the Q&A Thursdays and gotten very useful answers. Business for Bohemians, by Tom Hodgkinson- Anna recommended this book, and it’s been really useful to think about the creative contribution I’m trying to make in my career (beyond the first book), and the practical steps needed to make that succeed. I want to have a beer with the author. (BTW, add books to your Goodreads Want to Read bookshelf to help authors!) Before and After the Book Deal: A Writer’s Guide to Finishing, Publishing, Promoting, and Surviving Your First Book, by Courtney Maum- this reassuring and friendly book is really good at giving an overview of the whole process, illustrated with relatable stories and examples. The Creative Penn Podcast- Joanna Penn has a huge and comprehensive assortment of information for every aspiring writer. Good luck and keep writing! ---

Update, the newsletter is live!

Head over to Substack to read WE CAN FIX IT!

Hello world! Like many of us, I've spent 2020 locked away - in my case, writing my book, UNDER THE SKY WE MAKE, which I can't wait to share with you in March 2021.

As I'm wrapping up final edits and fact-checks on the book, I'm looking forward to starting new projects. On the agenda for 2021 will be an occasional newsletter on facing the climate crisis with facts, feelings, and action, where I'll share my latest research, writing, reflections, and projects, as well as what I'm reading, listening to, and enjoying, and answer reader questions. (Don't worry, I won't spam you- I'm aiming for monthly updates). I'd love to send you the inaugural copy when it launches, and to hear any suggestions for topics you'd like to see covered. Please sign up below. Thanks! P.S. For the full scoop on the newsletter, please head over to read more on Substack. This is a tough and thankless job, but science depends on it! Here are a few principles I keep in mind when suggesting (to journals that ask for them) or soliciting (when I'm an editor) peer reviewers.

When identifying reviewers for a particular paper, I try to find a balance of:

Where to find reviewers?

(Along those lines- if you’re publishing make sure you’re giving back to the community by serving as a peer reviewer and/or editor yourself! Read my guide to writing a solid peer review or how to get started, and register as a potential reviewer with journals in your field). Ethics:

See guidelines for picking reviewers: https://methodsblog.wordpress.com/2015/10/15/preferred-reviewers/ For the PNAS guidelines see here: http://m.pnas.org/site/authors/coi.xhtml Springer, Conflict of Interest: http://www.springer.com/authors/manuscript+guidelines?SGWID=0-40162-6-795522-0 Article on COI in medicine: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2246405/ I remember being confused about what was expected of scientific authorship in grad school. My mentor Pam Matson had a helpful rule of thumb: there are three things you can do to contribute to a scientific paper: (1) have the idea, (2) get the money, and (3) do the work. At least two of these three are required for authorship. (Thus, under this model, a PI who has an idea and gets funding to support a PhD student on that theme would be expected to be a coauthor on all resulting papers.) I appreciate having clear guidelines and expectations for authorship, so I was glad to come across the authorship guidelines from the Vancouver Convention. Basically, they recommend 4 criteria for authorship (all four criteria must be met for authorship): 1. Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND 2. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND 3. Final approval of the version to be published; AND 4. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This is the model I aim to follow in my collaborations. Thus, I expect myself and all authors to make a substantial intellectual contribution (#1) and contribute to writing and editing the manuscript (#2). I interpret #3 above as the lead (first) author has responsibility to solicit and integrate input from all authors in making revisions, and obtain their approval before sending to the journal. I interpret this responsibility as applying at three stages: 1. During drafting of a manuscript, until all authors approve the MS being submitted to the journal; 2. During peer review, when the lead author takes primary responsibility for addressing comments from peer review, with input from all authors, and gets approval from all authors for the version to re-submit to the journal (this stage repeated as necessary if there is more than one round of peer review); and 3. During copyediting, when the lead author shares the typeset and corrected final proof with all authors for their approval before submitting for processing and publication. I think all three of these stages are important in order to ensure that the last round (approval before publication) is sufficiently met, so that all authors are in a position to take ethical responsibility for the work (#4). (See my tips on how to work with revisions suggested by reviewers here.) When working on revisions, and especially with large and diffuse author groups, the lead author has to herd the cats and balance between giving everyone opportunity for input, and making decisions about the most appropriate direction for the paper (especially when coauthors or reviewers may have contradictory suggestions). After giving all authors a chance for input, during revisions the lead author might send around a version that incorporates changes suggested and say something like, “Thanks for all your comments, which have been incorporated in the attached version. I had to balance between suggestions X and Y, which I did by Z; I hope everyone is satisfied with this approach. I would like to submit on X date (eg 1 week in the future). Please reply with either (a) any critical changes needed for accuracy or (b) your approval to submit. Thanks!” It's especially essential to receive positive affirmation (i.e., a verbal or written OK to submit) from each author for the final version to be published. |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2023

|

KIM NICHOLAS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed