|

Note: This blog post now appears on the Road to Paris platform.

Johan Rockström of the Stockhölm Resilience Centre noted that the current text “still has the possibility of transformational change,” with the number one goal to limit warming as far below 2° as possible. Taking as a given the increasing risks posed by increasing temperatures caused by continued emissions, the panel focused on how to achieve the targets currently under discussion, linking it to language in the text that would make the goal consistent with science. Prof. Hans Schellnhuber of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research confirmed the benchmark that, for a decent chance of meeting a temperature target, the world has to get CO2 out of the system by 2050 for the 1.5 degree target, and by 2070 for 2 degrees. He stated this would require 2% reductions every year to decrease linearly to zero, further noting this was technically possible, and that Germany has been pursuing this goal faster than expected.  The current text calls for "GHG neutrality in second half of the century," which leaves the door open to the necessary zero carbon emissions, but does not ensure it. Several panelists raised concerns about the current “greenhouse gas neutrality” language. Prof. Kevin Anderson of the University of Manchester said the language of neutrality masks the need for “negative emissions,” removal of carbon from the atmosphere using largely unproven means. Schellnhuber echoed the concern that negative emissions were a “gamble,” further stating that every country has to go for complete decarbonization by 2050 to meet the 1.5 degree target. Rockström agreed, stating that "decarbonization" was a better long-term qualitative goal than greenhouse gas neutrality. He further warned the audience that staying under 2 degrees is also about keeping carbon in rainforests and other ecosystems, a service that becomes riskier at higher temperatures due to feedbacks between the land and atmosphere. For any chance of 1.5°, Rockstrom continued that the richest nations (such as the EU, US, Australia, and other OECD countries) need to lead the charge to zero fossil fuel use at 2030, in order to leave some space in the carbon budget for developing countries to transition slightly more slowly to decarbonization. He noted that this is a very ambitious target, which the current climate pledges, or intended nationally determined contributions, do not yet meet. Kevin Anderson stressed the critical nature of aligning national pledges with the agreed target over time through a robust, regular review process going forward, which Rockstrom suggested could occur every 2-3 years, as part of regular Conference of the Party meetings. Joeri Rogelj of IIASA noted that scenarios consistent with the 1.5 target are expected to achieve global peak emissions by 2020. Noting this date leaves no time to waste, Rogelj said, “We must start rapid emission reductions, and not count on carbon capture and storage later.” As everyone at Le Bourget anxiously awaits the next round of text, Prof. Schellnhuber cited his long experience with the climate negotiations process, saying that the second to last text that we now have available was “always stronger” than the final text, as parties had to compromise to reach agreement. He called the current text “extremely progressive, believe it or not,” though he warned that even the current softer goal of “greenhouse gas neutrality after mid-century” could disappear in the final wranglings over the next few hours. Looking ahead, journalist Mark Hertsgaard asked “What has to happen in the next 18 months, not just the next 18 hours, from all governments to be realistic about 1.5?” Kevin Anderson cited a role for individuals, noting a new report showing that 50% of global CO2 emissions come from just 10% of the population. He said this means that energy demand (reducing high-CO2 activities like flying) needs to be reduced by high emitters, including “most of us in this room.” Schellnhuber said that the Paris Agreement will send a message to civil society- and it will be the work of business, cities, investors, and all of us to finish the job. He concluded that COP21 has to make the 1.5 to 2 degree target consistent with long-term actions, and “if they do their job, we'll be fine."

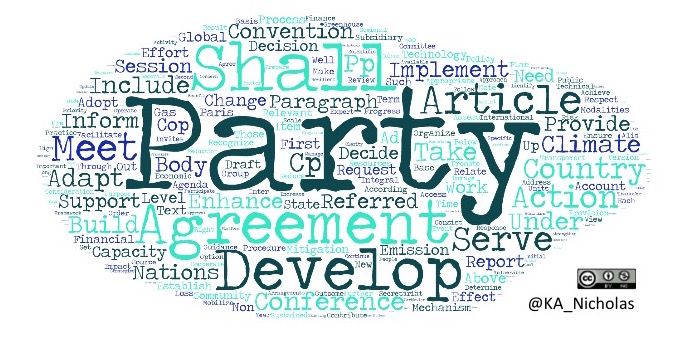

The new text of the Draft Paris Agreement dropped at 21h on Thursday at the UN climate summit. From the word cloud above, you can see that it's an agreement that shall develop into a party. And where nations should take action to meet, adapt, build, support, and implement!

There was a frantic rush for printers and the document center as delegates, observers and press scurried to take in the new document, which COP President Laurent Fabius said was the second to last text, aiming to finalize tomorrow into the "universal, legally binding, ambitious, fair, lasting agreement that the world's waiting for. I think we'll make it."

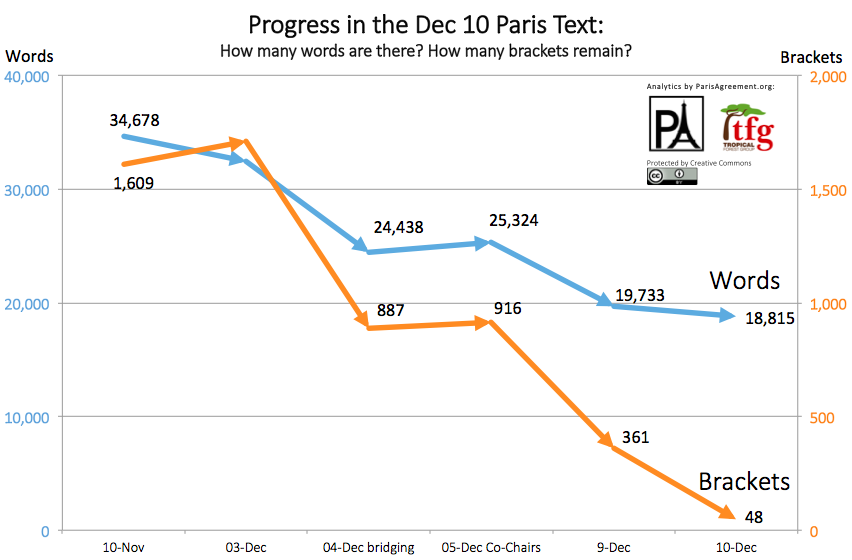

Analysis by my friends at parisagreement.org (below) shows that we're down to just 48 brackets, or points of contention. The Parties are now hashing these out in a closed-door "solutions indaba", to the disappointment of keen observers.

While we wait to see what will emerge in the morning, you can see a helpful ongoing analysis of the text evolution (what's in, what's out) at the Deconstructing Paris blog, and catch up on who's said what at the negotiations (that were open to observers) with accuracy, insight, and funny GIFs at the Google doc run by COP21 heroes @LaingHamish and @ryanmearns. For the full GIF-based reaction to COP21, try Leehi's ParIsThisIt?

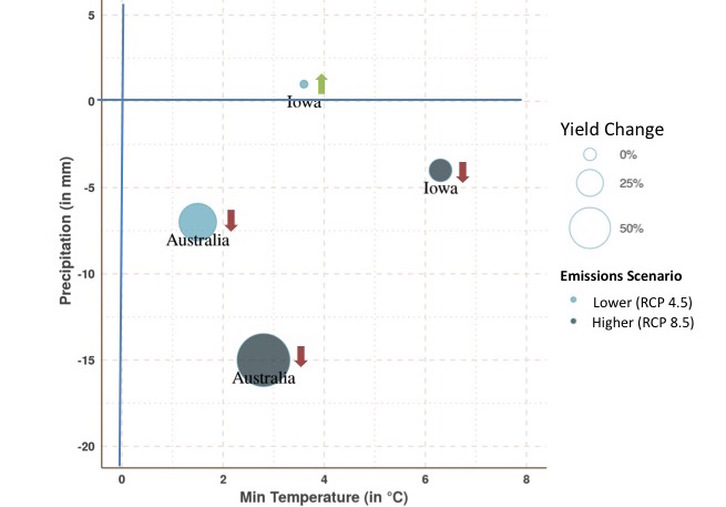

Draft Paris Agreement Word Cloud by Kimberly Nicholas is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Our new study shows trouble ahead for feeding the world under a warmer climate, with yields for staple grains declining more sharply with greater warming if high emissions of greenhouse gases continue. If emissions are reduced to the level represented by the current climate pledges at the start of the Paris summit (where carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere stabilize around 550ppm), yields of corn in Iowa are projected to be similar to today (or even experience a slight increase of 6%). However, continued high emissions leading to greater warming would be expected to produce a 21% decline in yields. The news is worse for wheat yields in southeast Australia. This region already struggles with drought in a crop system that relies on rainfall, and climate models consistently project the area will get warmer and drier in the future. This combination spells potential yield declines of 50% under lower warming, and 70% under greater warming: extremely challenging conditions for continued wheat production in the region. Average projected changes for temperature, precipitation, and yields for wheat in Southeastern Australia and maize (corn) in Iowa under two scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions. Under the lower scenario, maize yields in Iowa increase 6%, while they decline 21% under higher emissions. Wheat yields in Southeast Australia are projected to decrease 50% under lower warming, and 70% under higher warming, exacerbated by drier conditions in the future. Projections are for the end of the century (2070-2100) compared with a historical baseline (1951-1980). An interactive version of this figure, with results for each climate model and scenario, is available here. Figure by Martin Jung using data from Ummenhofer et al. 2015. The study, published in the Journal of Climate, found that yields of staple cereal were very sensitive to changes in climate. In particular, we found that, on average, each increase of 1°C (1.8°F) in temperature resulted in a yield decrease of 10% for corn in Iowa, and 15% for wheat in Southeastern Australia. This means that limiting warming through reduced heat-trapping pollutants is important to maintain the productivity of today’s breadbaskets. Both crops were also highly influenced by rainfall. Each decrease in precipitation of 10mm (0.39 inches) resulted in a yield decrease of 12% for Iowan corn and 9% for Australian wheat. Australia is predicted to experience substantially drier conditions in the future, which contributes to the large yield declines projected. In addition to average yields, we examined the conditions that produced extremely high and extremely low yields in the past, since weathering these extremes are important for farmers to maintain viability. Our analysis showed that, in the past, high yields of corn in Iowa tended to happen in particularly rainy years, with dry years spelling trouble for corn yields. Fortunately for Iowa, the changes projected for rainfall in the future are relatively small, with little difference between the higher and lower greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. However, the six computer models we used to simulate future climate make different projections, with half predicting a slight increase in rainfall (and therefore an increase in future good yields), while others predict somewhat less rain (and more tough years for corn). High yields of wheat in southeast Australia were also associated with wetter years in the past. Such years are consistently predicted to become less common in the future: all climate models and emissions scenarios agree in predicting a major increase in extremely bad years, where more than two-thirds of years will have yields 20% or more below today’s average.

The implications of this work are that increasing temperatures and rainfall variability from greater greenhouse gas emissions pose increasing challenges for agriculture. Research led by our colleague David Lobell has shown that this trend is already evident today: there has been a yield decline for cereal crops since the 1980s of 10% for every 1°C (1.8°F) warming. Many recent studies confirm the potential for yield declines for staple cereal crops under greater warming, especially for wheat. Different regions around the world are poised to experience climate change differently, and the risks depend on both the climate change experienced, and the human systems on the ground there. In the case of Iowan corn, the combination of the farming system and the climate poses less of a risk than wheat production in Australia, which is closer to its limits of viability today. Farmers can prepare for changes already underway, with more projected for the future, but the larger the changes experienced, the more difficult they will be to manage. This reinforces the climate change adage to “manage what we can’t avoid and avoid what we can’t manage” by reducing the emissions of greenhouse gases. The research was conducted by an international team led by Dr. Caroline Ummenhofer of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts, USA. We studied historical yield and climate records to understand the effects of climate on crop yields in the past, and then projected how this is likely to change in the future. To do so, we used the latest climate models (six simulations developed by groups in France, Japan, the US, and Australia) and scenarios of future greenhouse gas emissions (a business-as-usual scenario of continuing high emissions of greenhouse gases, known as RCP 8.5, and a moderate stabilization scenario called RCP 4.5, which would involve emissions stabilizing at around 5 gigatons of carbon per year by the end of the century, compared with current emissions around 9 gigatons). |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2023

|

KIM NICHOLAS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed