|

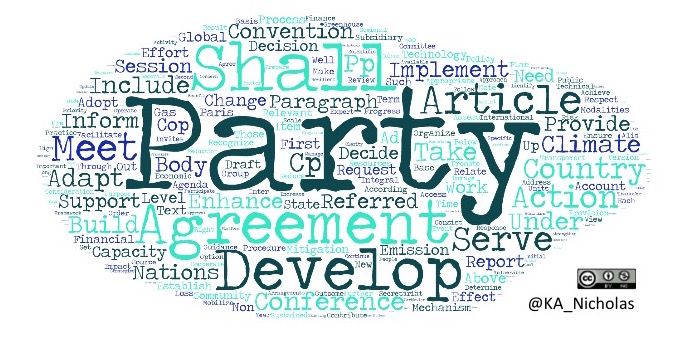

The new text of the Draft Paris Agreement dropped at 21h on Thursday at the UN climate summit. From the word cloud above, you can see that it's an agreement that shall develop into a party. And where nations should take action to meet, adapt, build, support, and implement!

There was a frantic rush for printers and the document center as delegates, observers and press scurried to take in the new document, which COP President Laurent Fabius said was the second to last text, aiming to finalize tomorrow into the "universal, legally binding, ambitious, fair, lasting agreement that the world's waiting for. I think we'll make it."

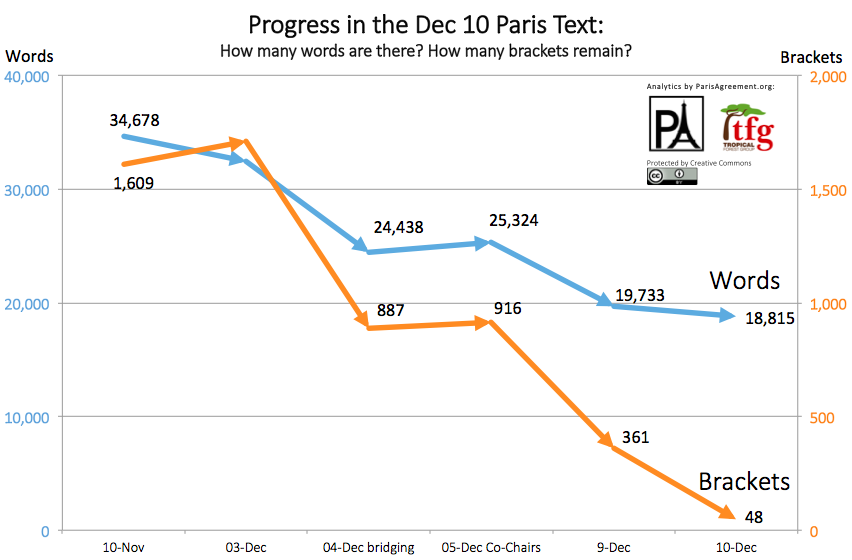

Analysis by my friends at parisagreement.org (below) shows that we're down to just 48 brackets, or points of contention. The Parties are now hashing these out in a closed-door "solutions indaba", to the disappointment of keen observers.

While we wait to see what will emerge in the morning, you can see a helpful ongoing analysis of the text evolution (what's in, what's out) at the Deconstructing Paris blog, and catch up on who's said what at the negotiations (that were open to observers) with accuracy, insight, and funny GIFs at the Google doc run by COP21 heroes @LaingHamish and @ryanmearns. For the full GIF-based reaction to COP21, try Leehi's ParIsThisIt?

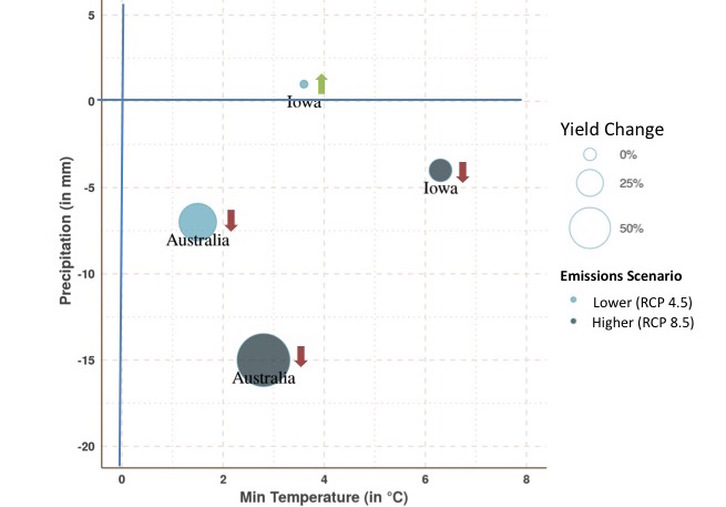

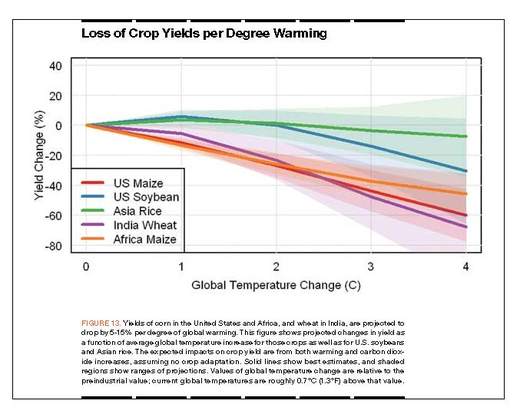

Draft Paris Agreement Word Cloud by Kimberly Nicholas is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Our new study shows trouble ahead for feeding the world under a warmer climate, with yields for staple grains declining more sharply with greater warming if high emissions of greenhouse gases continue. If emissions are reduced to the level represented by the current climate pledges at the start of the Paris summit (where carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere stabilize around 550ppm), yields of corn in Iowa are projected to be similar to today (or even experience a slight increase of 6%). However, continued high emissions leading to greater warming would be expected to produce a 21% decline in yields. The news is worse for wheat yields in southeast Australia. This region already struggles with drought in a crop system that relies on rainfall, and climate models consistently project the area will get warmer and drier in the future. This combination spells potential yield declines of 50% under lower warming, and 70% under greater warming: extremely challenging conditions for continued wheat production in the region. Average projected changes for temperature, precipitation, and yields for wheat in Southeastern Australia and maize (corn) in Iowa under two scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions. Under the lower scenario, maize yields in Iowa increase 6%, while they decline 21% under higher emissions. Wheat yields in Southeast Australia are projected to decrease 50% under lower warming, and 70% under higher warming, exacerbated by drier conditions in the future. Projections are for the end of the century (2070-2100) compared with a historical baseline (1951-1980). An interactive version of this figure, with results for each climate model and scenario, is available here. Figure by Martin Jung using data from Ummenhofer et al. 2015. The study, published in the Journal of Climate, found that yields of staple cereal were very sensitive to changes in climate. In particular, we found that, on average, each increase of 1°C (1.8°F) in temperature resulted in a yield decrease of 10% for corn in Iowa, and 15% for wheat in Southeastern Australia. This means that limiting warming through reduced heat-trapping pollutants is important to maintain the productivity of today’s breadbaskets. Both crops were also highly influenced by rainfall. Each decrease in precipitation of 10mm (0.39 inches) resulted in a yield decrease of 12% for Iowan corn and 9% for Australian wheat. Australia is predicted to experience substantially drier conditions in the future, which contributes to the large yield declines projected. In addition to average yields, we examined the conditions that produced extremely high and extremely low yields in the past, since weathering these extremes are important for farmers to maintain viability. Our analysis showed that, in the past, high yields of corn in Iowa tended to happen in particularly rainy years, with dry years spelling trouble for corn yields. Fortunately for Iowa, the changes projected for rainfall in the future are relatively small, with little difference between the higher and lower greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. However, the six computer models we used to simulate future climate make different projections, with half predicting a slight increase in rainfall (and therefore an increase in future good yields), while others predict somewhat less rain (and more tough years for corn). High yields of wheat in southeast Australia were also associated with wetter years in the past. Such years are consistently predicted to become less common in the future: all climate models and emissions scenarios agree in predicting a major increase in extremely bad years, where more than two-thirds of years will have yields 20% or more below today’s average.

The implications of this work are that increasing temperatures and rainfall variability from greater greenhouse gas emissions pose increasing challenges for agriculture. Research led by our colleague David Lobell has shown that this trend is already evident today: there has been a yield decline for cereal crops since the 1980s of 10% for every 1°C (1.8°F) warming. Many recent studies confirm the potential for yield declines for staple cereal crops under greater warming, especially for wheat. Different regions around the world are poised to experience climate change differently, and the risks depend on both the climate change experienced, and the human systems on the ground there. In the case of Iowan corn, the combination of the farming system and the climate poses less of a risk than wheat production in Australia, which is closer to its limits of viability today. Farmers can prepare for changes already underway, with more projected for the future, but the larger the changes experienced, the more difficult they will be to manage. This reinforces the climate change adage to “manage what we can’t avoid and avoid what we can’t manage” by reducing the emissions of greenhouse gases. The research was conducted by an international team led by Dr. Caroline Ummenhofer of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts, USA. We studied historical yield and climate records to understand the effects of climate on crop yields in the past, and then projected how this is likely to change in the future. To do so, we used the latest climate models (six simulations developed by groups in France, Japan, the US, and Australia) and scenarios of future greenhouse gas emissions (a business-as-usual scenario of continuing high emissions of greenhouse gases, known as RCP 8.5, and a moderate stabilization scenario called RCP 4.5, which would involve emissions stabilizing at around 5 gigatons of carbon per year by the end of the century, compared with current emissions around 9 gigatons). I'm excited and honored to be attending the climate summit in Paris as an accredited observer from Lund University. This is where nearly 200 countries will come together and aim to reach an agreement about how to change the path we're now on (a business-as-usual world headed for +4-5°C) to a more sustainable world that avoids the worst impacts of climate change.

This will be my first time attending the United Nations climate negotiations, and I am looking forward to learning more about the process and how to make my research more relevant to policy, as well as to serve as an advisor to the Youth in Landscapes initiative at the Global Landscapes Forum, and take part in the Anthronaut Experience- a virtual reality hackathon with scientists, artists, designers, and virtual reality experts to make climate science narratives a 3D experience. As I'm busy packing my bags, I'm gathering reading material for the 16-hour train ride to Paris. Here's what I'll be reading up on: General background:

Current perspectives:

Preparing for attending the meeting:

Keeping up with the negotiations in real time:

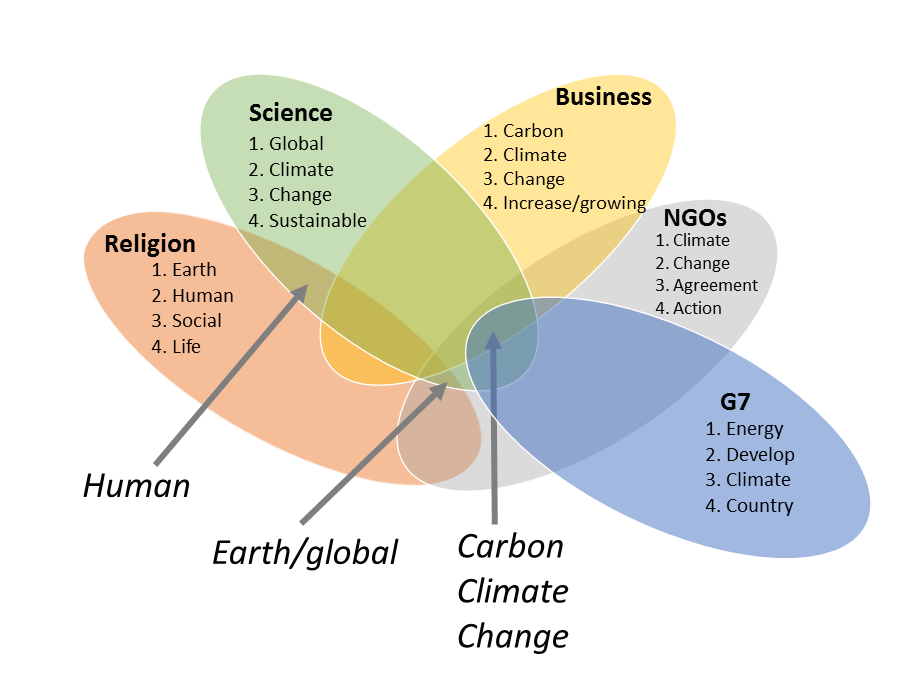

By Marius Sandvoll Weschke and Kimberly Nicholas The climate summit that will begin in Paris next week will attract delegates from more than 190 countries, all with the goal of signing an agreement to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. The whole world will have their eyes on Paris when the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP) is underway, and the pressure on the politicians and decision makers going to Paris is high, not only from their own governments and voters, but from many other parts of society. In particular, in recent months there has been a groundswell of statements on climate change from across sectors in society, from religious leaders, businesses, and scientific groups, to non-governmental organizations and national leaders. These statements outline the most important issues that their authors feel the Paris meeting should address. Among the statements gaining the most attention the last year an encyclical from Pope Francis, urging the world’s 1.2 billion Catholics to join the fight against climate change. A statement like this resonates far beyond the religious community, and it was portrayed in the media as a signal to politicians to pick up the pace on climate action. While the high-level United Nations process can make climate policy seem like a distant issue, these statements show that a vast number of people and interest groups are keenly invested in the process. We were interested in the key messages these diverse groups agree on. To analyze this, we analyzed 11 statements on climate change from religious groups, science, businesses, NGOs and the G7. The goal was to find out if the different groups speak the same language. That is, we wanted to see if the most commonly used words in the different statements overlap, which would indicate similar perspectives on the issue of climate change. We used an online word cloud generator to identify the 25 most commonly used words in each statement, and looked for words that were shared between statements (Figure 1).  Figure 1: Quantitative word analysis of 11 climate change statements originating from statements in five categories: four religious statements, three scientific, two business, one NGO consortium, and the G7 leaders. The four most commonly used words within each category are shown in each bubble, while the words that are overlapping between categories are marked with arrows. See footnote (1) for list of statements analyzed. Our analysis showed the words ‘carbon’, ‘climate’, and ‘change’ are all among the most used words for science, business, NGOs and G7, but not the religious statements, indicating a technical and problem-oriented approach among these groups. The word ‘Earth’/’global’ shared similar ground between religion, science and NGOs, indicating a political or philosophical outlook shared by these groups. Surprisingly, religion and science shared the word ‘human’ among their most used words, indicating a shared worldview seeing people as both the cause and the solution to the problem of climate change. In the beginning of the study we hypothesized that there would be words that would be found among all categories, but as the figure shows, there was no word that all five sectors used most commonly. However, the existence of these statements still sends a strong message that the international community - from religious groups to businesses and from scientists to NGOs - wants their leaders and policymakers to focus on stronger action, leading to solutions to tackle human-induced carbon emissions driving climate change in Paris. At the same time, the religious perspectives highlight the social values these choices represent, and how fundamental they are to our way of life. Statements Analyzed: Religious statements: Pope Francis’ Encyclical (http://tinyurl.com/ptcm9bz), A Buddhist Declaration on Climate Change (http://tinyurl.com/p9ge6xj), Islamic Climate Declaration (http://tinyurl.com/nqg98o7), A Rabbinic Letter on the Climate Crisis (http://tinyurl.com/qcyzmqg). Scientific statements: Earth Statement (http://tinyurl.com/nqw7d9b), Our Common Future under Climate Change (http://tinyurl.com/q5oy4x5), Planet under Pressure (http://tinyurl.com/7mvc9vq) Business statements: Institutional Investment Group on Climate Change (http://tinyurl.com/oaf6ooz), The World Bank: Putting a Price on Carbon (http://tinyurl.com/nrkagpx). NGO statement: Paris 2015: getting a global agreement on climate change (http://tinyurl.com/mhbqt2r). National leaders: Leaders’ Declaration G7 Summit 2015 (http://tinyurl.com/nmuagfd) This post summarizes research by Marius Sandvoll Weschke and Kimberly Nicholas presented at the Transformations conference held in Stockholm, October 2015.

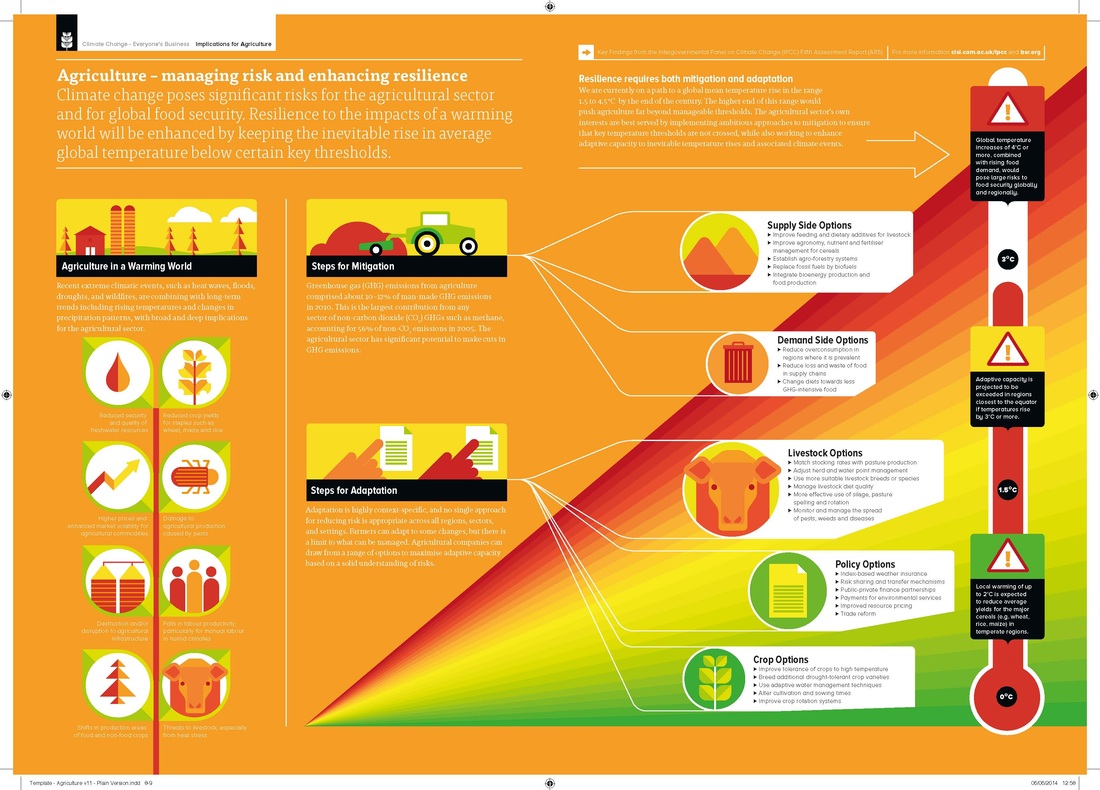

Read an interview with Marius about this work in the Finnish newspaper Kyrkpressen here. I was recently contacted by a Swedish high school student writing a senior thesis with some questions about climate change and food production. Here are their questions, and my answers. 1. What effect does global warming have on food production? What kind of impact does this effect have on rich and poor countries? In general for most major food crops, increasing temperatures decrease yields. The more warming, the greater yield loss. About 2/3 of food that people eat worldwide (measured in calorie production) comes from 4 crops: wheat, maize, rice, and soybean. These crops are sensitive to temperature, as you can see below. Here rice is not so much affected (the green line does not decline very much with warming), and soybean can also tolerate some higher temperatures (the blue line does not drop much until more than 2° of warming occurs), but wheat (purple line) and maize (called corn in the US; red and orange lines) start to experience big yield losses that increase with more warming. The effect of warming on crops depends on physics (how much does the atmosphere warm) and biology (how do crops respond to warming), as well as social systems (how well can people cope with change and what resources do they have to do so- this can include traditional knowledge as well as technology like irrigation). Even rich countries can be affected. For example, I have just published a paper with colleagues that shows that wheat yields in Australia are likely to decline 50-70% with high warming from continued heat-trapping pollutants (greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide). 2. What actions/solutions are there to make the impact as little as possible? What have the countries done so far to prevent this? There are many ways to reduce climate change, for individuals, organizations like schools, communities, businesses, and countries. Individuals can consider their carbon footprint. Some of the biggest ways to reduce this are to eat less meat or adopt a vegetarian diet, minimize travel especially air travel, and choose to have fewer children. Organizations can assess their resource use and find ways to focus on delivering the desired services (like education) with less resource inputs. Fundamentally, to reduce the risks of climate change, the world needs to move towards a goal of zero carbon emissions. This means we need to stop burning fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas, which contain a lot of carbon that turns into the heat-trapping pollutant carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. How we use land to grow food is also a major contributor. Your question about what countries are doing is very timely. The international process around climate change is coordinated by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. There will be a meeting in Paris (called COP21) starting in November where new treaties are negotiated. Many countries have made good progress. One example that got recent attention was the deal between the US and China, which you can read about here. However, much more work needs to be done to meet the targets for limiting climate change to 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Right now, the countries are making statements about what their commitments will be to reduce emissions. You can read more here for an overview, and here for Europe. 3. Are there countries that can have a positive impact due to global warming? Yes, some areas and some sectors are likely to benefit from climate change. For example, it may be possible to grow more crops in Canada and Russia and other northern areas if they have longer growing seasons and warmer temperatures. Melting of Arctic ice could open up new shipping routes. However, the overall impacts of climate change are negative, and they outweigh the benefits. Many studies have shown that it will be cheaper to avoid climate change, than to spend money to adapt to change, especially if we continue high emissions and therefore experience a lot of warming, which will produce a lot of changes in the environment that are expensive and difficult or in some cases impossible to adapt to. 4. Are there any plans for the future? How will it look in the future when certain crops are lost or run out? The way I think about dealing with climate change is to “manage what we can’t avoid, and avoid what we can’t manage.” There are many options to deal with climate change in agriculture, like changing planting dates of crops, switching varieties, or using more irrigation. However, the more warming we experience, the more difficult it is to adapt, as the infographic from the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership briefing on the latest scientific studies from the shows. This is why it’s so critical to limit the amount of climate change we experience by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, so that the impacts are manageable.  Credit: Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, IPCC Climate Science Business Briefings, "Agriculture" infographic, 2014. There are 13 excellent visual summaries of the latest climate science here: http://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/business-action/low-carbon-transformation/ipcc-briefings/agriculture  It started out as a love affair to remember, but student street theater dramatized the breakup between Lund University and fossil fuels. It started out as a love affair to remember, but student street theater dramatized the breakup between Lund University and fossil fuels. Today for Global Divestment Day, along with hundreds of events organized worldwide, my students in Lund and others in Fossil Free Sweden held a street theater performance dramatizing the impending breakup of a relationship that has turned destructive: the connection between Lund University and fossil fuels. They asked me to give a short speech on the science of climate change and the connection with divestment. Speech text follows. Thank you to my students for inviting me here, and to all of you for being here. I’m Kim Nicholas, Associate Professor of Sustainability Science at the Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies. I’m here representing the scientific perspective on the urgency of climate change. Based on this urgency, I’m also here representing many of my colleagues, fellow faculty across departments and disciplines, who are joining together with an open letter urging the board at Lund University to comprehensively divest from fossil fuels with all due speed. Earth system scientists are like doctors, taking the pulse of the planet. And like doctors, when we see something from our measurements that worries us, we owe it to our patients to speak up. To give you my diagnosis upfront: science tells us that the climate is warming, it’s caused by our activities, we’re sure, it’s bad- and most importantly, that we can fix it, which is why we’re here today. For decades now, my colleagues and I are seeing that something is wrong with the patient Planet Earth. We see it in every corner of the globe- from melting ice sheets, to my own research studying how the climate affects food production. I am truly worried about how climate change is already decreasing crop yields and quality around the world. We have already seen a decline in cereal yields of 10% for every 1°C temperature increase since 1980.

Continuing on our current path of fossil fuel emissions produces some truly terrifying risks. The more carbon we emit, the more warming we expect, and the more severe, widespread, and irreversible the impacts. This is the conclusion of scientists regarding impacts on food production and water access, on natural habitat and human health.

This means that unchecked climate change limits our options for a good life, and makes such a life further out of reach of those around the world whose basic needs are not met today. So how do we avoid this risky future? It is a big challenge, but we have solved big challenges before. It is late in the game, but we are not too late. We have an opportunity to act now, and we must seize this opportunity. How do we “fix” climate change? There’s a very simple answer. There is widespread scientific agreement that, to reduce the risks we face, we need to limit warming to 2°C. To meet this target, just like we have a home budget to live within our means, the planet’s atmosphere has a budget of carbon dioxide. There are five times more fossil fuel reserves than the atmosphere can afford to absorb without exceeding the danger zone of warming. Meeting our carbon budget and avoiding dangerous warming means that the majority of fossil fuel reserves need to stay in the ground. If these reserves are burned according to current business plans, we are facing very serious risks. We need to pursue every option we have today to make a good life, a healthy life full of opportunities, one that does not run on carbon. This is why continued investment by Lund University in companies that profit from fossil fuels flies in the face of science. The research carried out here, and at other universities around the world, clearly shows the risks. It is logically inconsistent for Lund University to ignore the knowledge it is helping to produce in guiding its own management choices. Personally, I believe it is also ethically inconsistent for Lund University to continue its investment in fossil fuels. Even if its fossil fuel holdings are small, about 1% of funds, these investments are out of line with the ideals of a university like Lund. What is the purpose of a university? Lund University’s mission statement is to “understand, explain and improve our world and the human condition.” Universities are a place where we confront the sometimes very big gap between our highest ideals, and the imperfect world we see around us every day. Universities exist to help close that gap: to innovate, to create an example of how things can be better. With divestment, we have an opportunity to do just that. The faculty of Lund University are here to teach and to challenge our students. But sometimes our students challenge us, and question our assumptions- and this is a challenge we must face. Now our students are speaking with a clear voice: their future is at risk, and they want their university to lead the way to something better. I want to be a part of that University as well, one that not only supports the best research, but also supports putting those findings into practice in its own actions. The students I teach in the LUMES program come to Lund from 30 different countries around the world. They come because Sweden, and especially Lund University, has a reputation as a global leader in sustainability. I came here myself from California for that reason. There is a growing global movement for a better future, and I want Lund University to lead the way there. To walk this path, we call on the Lund University Board to join others around Sweden and the world in comprehensive divestment from fossil fuels.

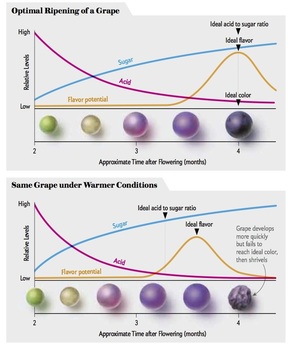

While research is ongoing to try to understand how the more than 1,000 aroma compounds identified in wine affect our flavor perception, many compounds appear to be sensitive to climate, particularly in the later stages of grape ripening. Some desirable compounds like rotundone, which gives Syrah its typical black pepper aroma, appear to accumulate more at cooler sites and in cooler years, so warmer-climate Syrahs have less of this character.  My parents' vineyard in the hills above Sonoma. My parents' vineyard in the hills above Sonoma. Winegrowers and winemakers have many options to adapt to warming climates. Growers are experimenting with new wine regions, cooler locations within existing regions (such as moving from warmer valleys to cooler hillsides), trying new varieties better suited to warmer conditions, and farming methods that provide more shade on the fruit. Winemakers can use approaches including alcohol removal and acid addition to improve wine balance. Steps like these can go a long way towards preserving great wines under climate change. Ultimately, though, there are economic and biophysical limits to this adaptation. There are also cultural limitations: the know-how and sense of place that growers cultivate along with the land over generations of family farming is not easily moved, and consumers have come to expect a distinct flavor profile from wines from their preferred regions. Great wine is grown, not made; it reflects its place of origin. If the climate changes even a little bit, local knowledge and skills that have taken generations to hone can become less relevant, even in familiar territory. But the changes we’re facing in climate are not small ones. Under our current trajectory of fossil fuel use, scientists project that the global average temperature will increase 4.7 to 8.6°F (2.6 to 4.8°C) over the next few generations. Even the low end of this range would be the difference in annual average temperatures between the winegrowing regions of Napa and Fresno today. Currently, Cabernet grapes from cooler Napa are worth more than 10 times as much as those from Fresno- a difference of over $3,000 a ton. Wine illustrates our deep reliance on nature to provide us with everything we need to live, and many of the things that make life worth living. We are in a moment of critical climate choices. Choosing to limit climate change gives us more options for a more healthy, thriving, fair, and delicious world- including more of the traditional flavors of your favorite wines.

As Diana Liverman wrote in the Washington Post, focusing on only the grim projections along our current trajectory overwhelms and depresses students, and makes them feel powerless to act. Rather than rallying them to unite against a negative future, this approach actually decreases the motivation that drove many of them to study the environment in the first place. Surely this is not why professors want to teach, to extinguish rather than fuel their student's fires.

Fortunately, there are solutions to turn the tide on climate change. As the world gears up for a UN conference in Paris in December 2015, where all countries are supposed to reach an agreement about greenhouse gas emissions, there has been a recent flurry of climate action and proposals, from the US-China climate deal to limit carbon emissions to grassroots campaigns to divest- moving financial investments away from fossil fuels. I've designed a teaching activity for master's students in my Earth Systems Science course to discuss and debate a range of climate change solutions. It fits within the framework I've used to design my teaching on climate change, which consists of five points that I first heard articulated in a lecture by Jon Krosnick at Stanford, based on his research with colleagues: it's warming, it's us, we're sure, it's bad, and we can fix it. People need to understand all of these points to get the whole picture of what climate change is, why it matters, and to be motivated to address it. It's essential to include the last point to leave students inspired rather than depressed.

*Update: Here is the Road to Paris story that resulted from this project, as well as my own Storify of the People's Climate March in Lund and Copenhagen. * I'm excited to share here a guest post written by Michelle Kovacevic, describing a new initiative I'm supporting to highlight the diversity and passion of people around the world supporting action to fight climate change. (As background: The 2014 Climate Summit is taking place in New York starting 23 September, convened by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon. This meeting will be attended by over 120 heads of state, who have been asked to announce their plans and policies to "reduce emissions, strengthen climate resilience, and mobilize political will for a meaningful legal agreement in 2015" at the December 2015 climate meeting in Paris (Conference of the Parties 21). I recommend the Road to Paris blog for great background reading on this process and its significance.) Please read on, participate, and share with your networks! -Kim  Image by Michelle Kovacevic Image by Michelle Kovacevic "From Melbourne to Lagos and Rio de Janeiro, this Sunday, September 21, the world will see the biggest-ever mobilization of people who want to see action against climate change: http://peoplesclimate.org/global/ The International Council of Science, through its Road to Paris blog, wants to create a global portrait of people passionate about climate change who are taking actions to make a difference. Are you planning to attend the People's Climate March in your city (global guide here), or in your own backyard? We were hoping you could help us compile a Humans of New York-style showcase of human stories about positive climate action around the world. All we're asking is for you to talk to 5 people at your city march and ask them:

-What positive climate action have they seen or been involved in? -Why are they marching? -Why do they care about climate change? -Why is it important to tackle climate change? Take a cool photo of them and the most interesting and positive story/quote you get while talking to each person and post on your social media account (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, etc.) with the tag #peopleofclimate #PCM. We will be following these hashtags and posting the best stories on the Road to Paris platform on Monday. Remember, like Humans of New York, keep the stories/quotes short, sweet and actionable. Thanks for helping us showcase the huge diversity of possible climate actions and people making a difference! Suggested social media posts: Attending #PCM? Post selfie and answer "What positive climate action have you seen/been involved in? tag #peopleofclimate" @road2paris Facebook/G+/LinkedIn Attending the Peoples Climate March in your city? Post a photo of yourself or your friends at your city march with an answer to the question "What positive climate action have you seen or been involved in?". Tag with #peopleofclimate #PCM so we can showcase the huge diversity of climate actions and people making a difference. For more information about this initiative, contact Denise Young ([email protected]) and Michelle Kovacevic ([email protected])." (Text above in quotations written by Michelle Kovacevic) |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2023

|

KIM NICHOLAS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed