|

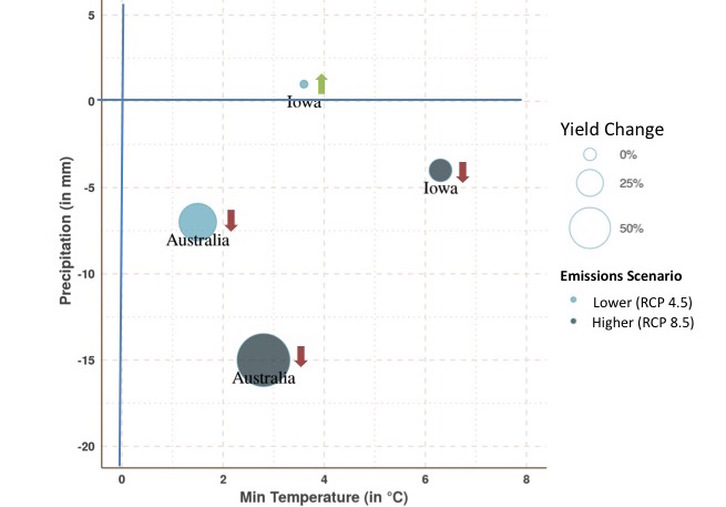

Our new study shows trouble ahead for feeding the world under a warmer climate, with yields for staple grains declining more sharply with greater warming if high emissions of greenhouse gases continue. If emissions are reduced to the level represented by the current climate pledges at the start of the Paris summit (where carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere stabilize around 550ppm), yields of corn in Iowa are projected to be similar to today (or even experience a slight increase of 6%). However, continued high emissions leading to greater warming would be expected to produce a 21% decline in yields. The news is worse for wheat yields in southeast Australia. This region already struggles with drought in a crop system that relies on rainfall, and climate models consistently project the area will get warmer and drier in the future. This combination spells potential yield declines of 50% under lower warming, and 70% under greater warming: extremely challenging conditions for continued wheat production in the region. Average projected changes for temperature, precipitation, and yields for wheat in Southeastern Australia and maize (corn) in Iowa under two scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions. Under the lower scenario, maize yields in Iowa increase 6%, while they decline 21% under higher emissions. Wheat yields in Southeast Australia are projected to decrease 50% under lower warming, and 70% under higher warming, exacerbated by drier conditions in the future. Projections are for the end of the century (2070-2100) compared with a historical baseline (1951-1980). An interactive version of this figure, with results for each climate model and scenario, is available here. Figure by Martin Jung using data from Ummenhofer et al. 2015. The study, published in the Journal of Climate, found that yields of staple cereal were very sensitive to changes in climate. In particular, we found that, on average, each increase of 1°C (1.8°F) in temperature resulted in a yield decrease of 10% for corn in Iowa, and 15% for wheat in Southeastern Australia. This means that limiting warming through reduced heat-trapping pollutants is important to maintain the productivity of today’s breadbaskets. Both crops were also highly influenced by rainfall. Each decrease in precipitation of 10mm (0.39 inches) resulted in a yield decrease of 12% for Iowan corn and 9% for Australian wheat. Australia is predicted to experience substantially drier conditions in the future, which contributes to the large yield declines projected. In addition to average yields, we examined the conditions that produced extremely high and extremely low yields in the past, since weathering these extremes are important for farmers to maintain viability. Our analysis showed that, in the past, high yields of corn in Iowa tended to happen in particularly rainy years, with dry years spelling trouble for corn yields. Fortunately for Iowa, the changes projected for rainfall in the future are relatively small, with little difference between the higher and lower greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. However, the six computer models we used to simulate future climate make different projections, with half predicting a slight increase in rainfall (and therefore an increase in future good yields), while others predict somewhat less rain (and more tough years for corn). High yields of wheat in southeast Australia were also associated with wetter years in the past. Such years are consistently predicted to become less common in the future: all climate models and emissions scenarios agree in predicting a major increase in extremely bad years, where more than two-thirds of years will have yields 20% or more below today’s average.

The implications of this work are that increasing temperatures and rainfall variability from greater greenhouse gas emissions pose increasing challenges for agriculture. Research led by our colleague David Lobell has shown that this trend is already evident today: there has been a yield decline for cereal crops since the 1980s of 10% for every 1°C (1.8°F) warming. Many recent studies confirm the potential for yield declines for staple cereal crops under greater warming, especially for wheat. Different regions around the world are poised to experience climate change differently, and the risks depend on both the climate change experienced, and the human systems on the ground there. In the case of Iowan corn, the combination of the farming system and the climate poses less of a risk than wheat production in Australia, which is closer to its limits of viability today. Farmers can prepare for changes already underway, with more projected for the future, but the larger the changes experienced, the more difficult they will be to manage. This reinforces the climate change adage to “manage what we can’t avoid and avoid what we can’t manage” by reducing the emissions of greenhouse gases. The research was conducted by an international team led by Dr. Caroline Ummenhofer of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts, USA. We studied historical yield and climate records to understand the effects of climate on crop yields in the past, and then projected how this is likely to change in the future. To do so, we used the latest climate models (six simulations developed by groups in France, Japan, the US, and Australia) and scenarios of future greenhouse gas emissions (a business-as-usual scenario of continuing high emissions of greenhouse gases, known as RCP 8.5, and a moderate stabilization scenario called RCP 4.5, which would involve emissions stabilizing at around 5 gigatons of carbon per year by the end of the century, compared with current emissions around 9 gigatons).  LUMES beekeepers Dora Adams and Christoph Aberle prepare me and LUCID PhD students Molly MacGregor and Henner Busch to visit their beehive at Stenkrossen in Lund. Photo: Teresa Rauscher. LUMES beekeepers Dora Adams and Christoph Aberle prepare me and LUCID PhD students Molly MacGregor and Henner Busch to visit their beehive at Stenkrossen in Lund. Photo: Teresa Rauscher. Last week, I visited the "Vi odlar" ("we grow!") garden in Lund, to get a tour of the beehive started as a LUMES "Making Change Happen" project by Dora Adams, Christoph Aberle, and Shrina Kurani.

Several LUMES students have been involved in getting salvaged materials (including the repurposed bathtub/veggie planters shown here) and working in the garden, which is a community meeting space and youth project supported through Lund Municipality and other organizations, co-organized by LUMES alum Teresa Rauscher. A local artist has built the tornado sculpture behind us, envisioned as an interactive monument to consumerism (people can come by and add items they no longer need.) The garden is open this summer for visitors to drop-in to learn more about urban gardening and beekeeping- stop by on Wednesdays from 17:00-19:00 at Stenkrossen, Kastanjegatan 13, Lund. |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2023

|

KIM NICHOLAS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed