|

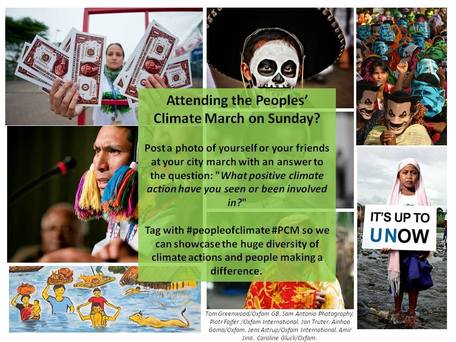

*Update: Here is the Road to Paris story that resulted from this project, as well as my own Storify of the People's Climate March in Lund and Copenhagen. * I'm excited to share here a guest post written by Michelle Kovacevic, describing a new initiative I'm supporting to highlight the diversity and passion of people around the world supporting action to fight climate change. (As background: The 2014 Climate Summit is taking place in New York starting 23 September, convened by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon. This meeting will be attended by over 120 heads of state, who have been asked to announce their plans and policies to "reduce emissions, strengthen climate resilience, and mobilize political will for a meaningful legal agreement in 2015" at the December 2015 climate meeting in Paris (Conference of the Parties 21). I recommend the Road to Paris blog for great background reading on this process and its significance.) Please read on, participate, and share with your networks! -Kim  Image by Michelle Kovacevic Image by Michelle Kovacevic "From Melbourne to Lagos and Rio de Janeiro, this Sunday, September 21, the world will see the biggest-ever mobilization of people who want to see action against climate change: http://peoplesclimate.org/global/ The International Council of Science, through its Road to Paris blog, wants to create a global portrait of people passionate about climate change who are taking actions to make a difference. Are you planning to attend the People's Climate March in your city (global guide here), or in your own backyard? We were hoping you could help us compile a Humans of New York-style showcase of human stories about positive climate action around the world. All we're asking is for you to talk to 5 people at your city march and ask them:

-What positive climate action have they seen or been involved in? -Why are they marching? -Why do they care about climate change? -Why is it important to tackle climate change? Take a cool photo of them and the most interesting and positive story/quote you get while talking to each person and post on your social media account (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, etc.) with the tag #peopleofclimate #PCM. We will be following these hashtags and posting the best stories on the Road to Paris platform on Monday. Remember, like Humans of New York, keep the stories/quotes short, sweet and actionable. Thanks for helping us showcase the huge diversity of possible climate actions and people making a difference! Suggested social media posts: Attending #PCM? Post selfie and answer "What positive climate action have you seen/been involved in? tag #peopleofclimate" @road2paris Facebook/G+/LinkedIn Attending the Peoples Climate March in your city? Post a photo of yourself or your friends at your city march with an answer to the question "What positive climate action have you seen or been involved in?". Tag with #peopleofclimate #PCM so we can showcase the huge diversity of climate actions and people making a difference. For more information about this initiative, contact Denise Young ([email protected]) and Michelle Kovacevic ([email protected])." (Text above in quotations written by Michelle Kovacevic) What if the secret to writing successful research proposals were to go back to the basic lessons your fourth grade teacher taught you about writing? It can't possibly be that simple, can it?

I just had a lovely dinner with my smart & wise friend Harriet Bulkeley. One of many good pieces of advice she gave me (this one picked up by joining a conversation she overheard on a train!) is to think over the answer to four things before beginning a research proposal or project: 1. What do I want to do? 2. Who do I want to do it with? 3. Where do I want to do it? 4. Why do I want to do it? I said this sounded like a great way to teach research design to students, but as we discussed more, I realized researchers at every level could probably benefit from this advice, myself included. She noted that many people can only answer one of these questions when they approach a university research office or a funding agency with a research idea. They might hope that the answers will get clarified in working through the project, but this is rarely the case. In projects that haven't clarified these key points at the outstart are likely to get bogged down in these issues through the course of research. A great reminder to think through the basics before committing your precious and limited time. I just read a New York Times article (posted by @eric_mazur*) that inspired me to post last year's final exam for my new students on the first day of our Earth Systems Science class. I have always shared last year's final as a teaching tool in the weeks before the exam, because I think it's the best study guide for students to work through it on their own or in small groups as they prepare. (Plus, it removes any possibility for cheating, which could be a temptation if last year's students are expected to keep old exams private after getting them returned.) I post just the exam for a week or so, and then post a compilation of the best student answers from the previous year to give an idea of what an excellent exam would look like. My reasoning is that I want all students who work hard to do well on the exam, and they will do their best if they have a realistic model to work with. After all, the most important thing I'm trying to teach is not facts, but a way of thinking, in particular, using data to support claims; the more exposure students get to this, the better.

However, this article by Benedict Carey just made me think about exams in a new way- as "learning devices" that can be "the key to studying, rather than the other way around." Psychological research has shown that pretesting can change the way we think, helping to prepare our brains to better receive, process, and hold on to relevant information when it appears. Testing, it turns out, is a powerful way to overcome the "fluency illusion"- thinking that we know something better than we do, because we study it in a vacuum where no competing plausible ideas exist. When presented with challenging competing ideas on a test, we're forced to reason our way through them to show we've really learned. The article describes initial research by Elizabeth Ligon Bjork (who heads the fantastically named "Learning and Forgetting Lab" at UCLA) and Nicholas Soderstrom, who presented psychology students with pretests. They found that pretesting increased their final exam scores by 10% (which can be a difference between a grade of C and B in the American grading system, for example). The researchers didn't give their students the final exam on the first day, because they didn't want them to be overwhelmed. I'm not asking my students to sit down and take a 3 hour exam - just posting it for them as a study resource. I hope they find it useful- stay tuned! * Walk down memory lane: The first time I learned anything about teaching (the horribly pedagogic-sounding but very important field of pedagogy) was as a "Kindergarten Through Infinity" fellow as a master's student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This was an NSF K-12 program that matched STEM grad students (who brought science content knowledge) with primary and secondary school teachers (who were expert teachers) to design learning activities for students ages 5 through 18. It was here that I first heard about and was inspired by Eric Mazur, the Harvard physics professor who turned his teaching upside-down when he realized his traditional lectures weren't producing deep learning, even for extremely bright students. His solution was the Peer Instruction method. This was the first time I heard about Think-Pair-Share and other teaching techniques I'm still using. |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2023

|

KIM NICHOLAS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed