|

The new text of the Draft Paris Agreement dropped at 21h on Thursday at the UN climate summit. From the word cloud above, you can see that it's an agreement that shall develop into a party. And where nations should take action to meet, adapt, build, support, and implement!

There was a frantic rush for printers and the document center as delegates, observers and press scurried to take in the new document, which COP President Laurent Fabius said was the second to last text, aiming to finalize tomorrow into the "universal, legally binding, ambitious, fair, lasting agreement that the world's waiting for. I think we'll make it."

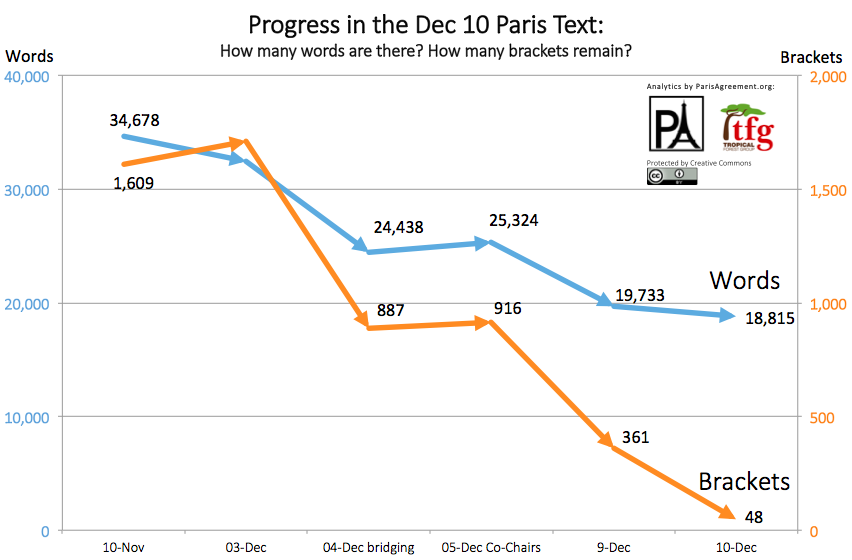

Analysis by my friends at parisagreement.org (below) shows that we're down to just 48 brackets, or points of contention. The Parties are now hashing these out in a closed-door "solutions indaba", to the disappointment of keen observers.

While we wait to see what will emerge in the morning, you can see a helpful ongoing analysis of the text evolution (what's in, what's out) at the Deconstructing Paris blog, and catch up on who's said what at the negotiations (that were open to observers) with accuracy, insight, and funny GIFs at the Google doc run by COP21 heroes @LaingHamish and @ryanmearns. For the full GIF-based reaction to COP21, try Leehi's ParIsThisIt?

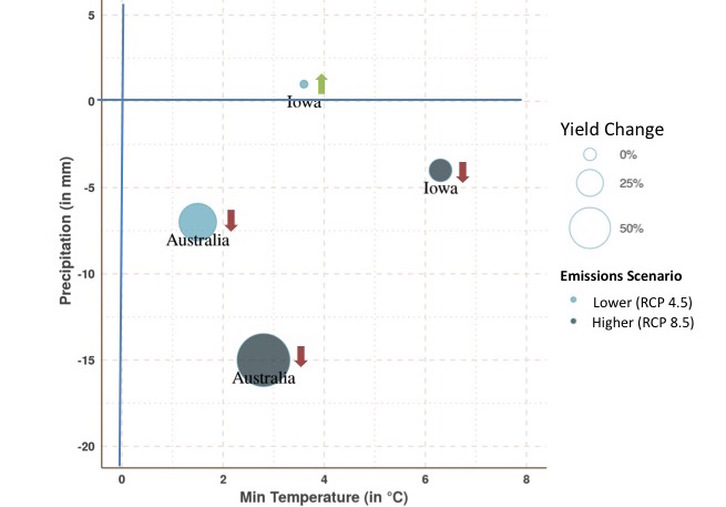

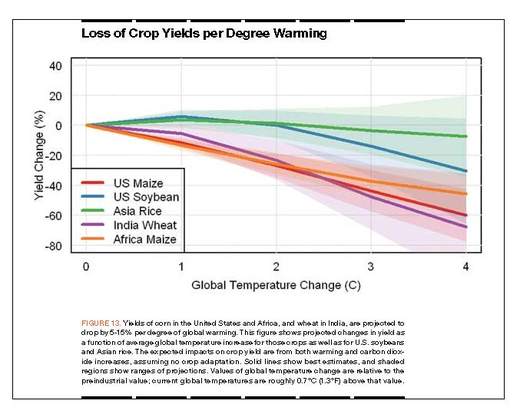

Draft Paris Agreement Word Cloud by Kimberly Nicholas is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Our new study shows trouble ahead for feeding the world under a warmer climate, with yields for staple grains declining more sharply with greater warming if high emissions of greenhouse gases continue. If emissions are reduced to the level represented by the current climate pledges at the start of the Paris summit (where carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere stabilize around 550ppm), yields of corn in Iowa are projected to be similar to today (or even experience a slight increase of 6%). However, continued high emissions leading to greater warming would be expected to produce a 21% decline in yields. The news is worse for wheat yields in southeast Australia. This region already struggles with drought in a crop system that relies on rainfall, and climate models consistently project the area will get warmer and drier in the future. This combination spells potential yield declines of 50% under lower warming, and 70% under greater warming: extremely challenging conditions for continued wheat production in the region. Average projected changes for temperature, precipitation, and yields for wheat in Southeastern Australia and maize (corn) in Iowa under two scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions. Under the lower scenario, maize yields in Iowa increase 6%, while they decline 21% under higher emissions. Wheat yields in Southeast Australia are projected to decrease 50% under lower warming, and 70% under higher warming, exacerbated by drier conditions in the future. Projections are for the end of the century (2070-2100) compared with a historical baseline (1951-1980). An interactive version of this figure, with results for each climate model and scenario, is available here. Figure by Martin Jung using data from Ummenhofer et al. 2015. The study, published in the Journal of Climate, found that yields of staple cereal were very sensitive to changes in climate. In particular, we found that, on average, each increase of 1°C (1.8°F) in temperature resulted in a yield decrease of 10% for corn in Iowa, and 15% for wheat in Southeastern Australia. This means that limiting warming through reduced heat-trapping pollutants is important to maintain the productivity of today’s breadbaskets. Both crops were also highly influenced by rainfall. Each decrease in precipitation of 10mm (0.39 inches) resulted in a yield decrease of 12% for Iowan corn and 9% for Australian wheat. Australia is predicted to experience substantially drier conditions in the future, which contributes to the large yield declines projected. In addition to average yields, we examined the conditions that produced extremely high and extremely low yields in the past, since weathering these extremes are important for farmers to maintain viability. Our analysis showed that, in the past, high yields of corn in Iowa tended to happen in particularly rainy years, with dry years spelling trouble for corn yields. Fortunately for Iowa, the changes projected for rainfall in the future are relatively small, with little difference between the higher and lower greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. However, the six computer models we used to simulate future climate make different projections, with half predicting a slight increase in rainfall (and therefore an increase in future good yields), while others predict somewhat less rain (and more tough years for corn). High yields of wheat in southeast Australia were also associated with wetter years in the past. Such years are consistently predicted to become less common in the future: all climate models and emissions scenarios agree in predicting a major increase in extremely bad years, where more than two-thirds of years will have yields 20% or more below today’s average.

The implications of this work are that increasing temperatures and rainfall variability from greater greenhouse gas emissions pose increasing challenges for agriculture. Research led by our colleague David Lobell has shown that this trend is already evident today: there has been a yield decline for cereal crops since the 1980s of 10% for every 1°C (1.8°F) warming. Many recent studies confirm the potential for yield declines for staple cereal crops under greater warming, especially for wheat. Different regions around the world are poised to experience climate change differently, and the risks depend on both the climate change experienced, and the human systems on the ground there. In the case of Iowan corn, the combination of the farming system and the climate poses less of a risk than wheat production in Australia, which is closer to its limits of viability today. Farmers can prepare for changes already underway, with more projected for the future, but the larger the changes experienced, the more difficult they will be to manage. This reinforces the climate change adage to “manage what we can’t avoid and avoid what we can’t manage” by reducing the emissions of greenhouse gases. The research was conducted by an international team led by Dr. Caroline Ummenhofer of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts, USA. We studied historical yield and climate records to understand the effects of climate on crop yields in the past, and then projected how this is likely to change in the future. To do so, we used the latest climate models (six simulations developed by groups in France, Japan, the US, and Australia) and scenarios of future greenhouse gas emissions (a business-as-usual scenario of continuing high emissions of greenhouse gases, known as RCP 8.5, and a moderate stabilization scenario called RCP 4.5, which would involve emissions stabilizing at around 5 gigatons of carbon per year by the end of the century, compared with current emissions around 9 gigatons). I'm excited and honored to be attending the climate summit in Paris as an accredited observer from Lund University. This is where nearly 200 countries will come together and aim to reach an agreement about how to change the path we're now on (a business-as-usual world headed for +4-5°C) to a more sustainable world that avoids the worst impacts of climate change.

This will be my first time attending the United Nations climate negotiations, and I am looking forward to learning more about the process and how to make my research more relevant to policy, as well as to serve as an advisor to the Youth in Landscapes initiative at the Global Landscapes Forum, and take part in the Anthronaut Experience- a virtual reality hackathon with scientists, artists, designers, and virtual reality experts to make climate science narratives a 3D experience. As I'm busy packing my bags, I'm gathering reading material for the 16-hour train ride to Paris. Here's what I'll be reading up on: General background:

Current perspectives:

Preparing for attending the meeting:

Keeping up with the negotiations in real time:

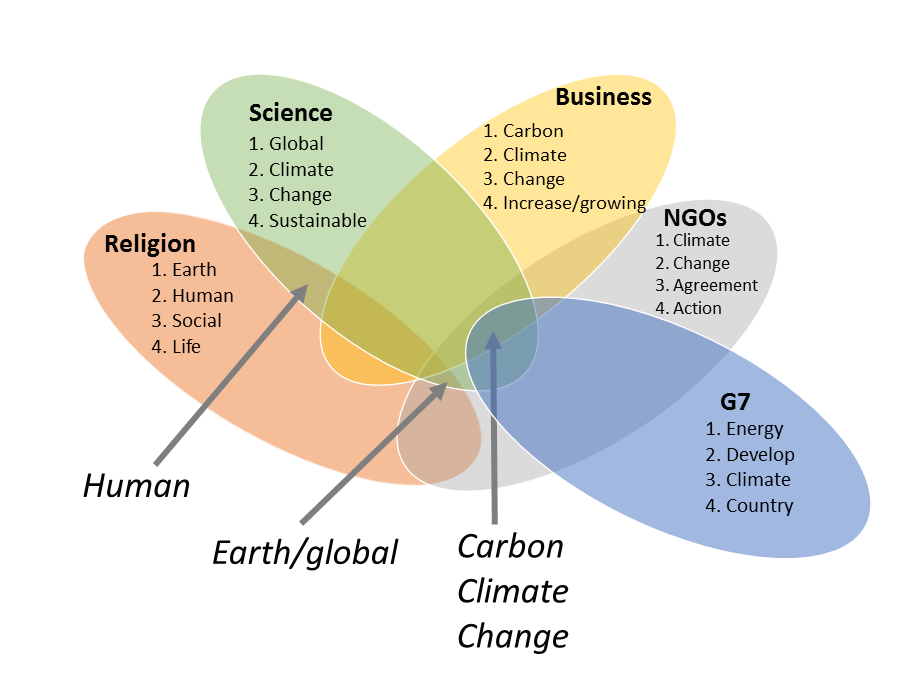

By Marius Sandvoll Weschke and Kimberly Nicholas The climate summit that will begin in Paris next week will attract delegates from more than 190 countries, all with the goal of signing an agreement to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. The whole world will have their eyes on Paris when the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP) is underway, and the pressure on the politicians and decision makers going to Paris is high, not only from their own governments and voters, but from many other parts of society. In particular, in recent months there has been a groundswell of statements on climate change from across sectors in society, from religious leaders, businesses, and scientific groups, to non-governmental organizations and national leaders. These statements outline the most important issues that their authors feel the Paris meeting should address. Among the statements gaining the most attention the last year an encyclical from Pope Francis, urging the world’s 1.2 billion Catholics to join the fight against climate change. A statement like this resonates far beyond the religious community, and it was portrayed in the media as a signal to politicians to pick up the pace on climate action. While the high-level United Nations process can make climate policy seem like a distant issue, these statements show that a vast number of people and interest groups are keenly invested in the process. We were interested in the key messages these diverse groups agree on. To analyze this, we analyzed 11 statements on climate change from religious groups, science, businesses, NGOs and the G7. The goal was to find out if the different groups speak the same language. That is, we wanted to see if the most commonly used words in the different statements overlap, which would indicate similar perspectives on the issue of climate change. We used an online word cloud generator to identify the 25 most commonly used words in each statement, and looked for words that were shared between statements (Figure 1).  Figure 1: Quantitative word analysis of 11 climate change statements originating from statements in five categories: four religious statements, three scientific, two business, one NGO consortium, and the G7 leaders. The four most commonly used words within each category are shown in each bubble, while the words that are overlapping between categories are marked with arrows. See footnote (1) for list of statements analyzed. Our analysis showed the words ‘carbon’, ‘climate’, and ‘change’ are all among the most used words for science, business, NGOs and G7, but not the religious statements, indicating a technical and problem-oriented approach among these groups. The word ‘Earth’/’global’ shared similar ground between religion, science and NGOs, indicating a political or philosophical outlook shared by these groups. Surprisingly, religion and science shared the word ‘human’ among their most used words, indicating a shared worldview seeing people as both the cause and the solution to the problem of climate change. In the beginning of the study we hypothesized that there would be words that would be found among all categories, but as the figure shows, there was no word that all five sectors used most commonly. However, the existence of these statements still sends a strong message that the international community - from religious groups to businesses and from scientists to NGOs - wants their leaders and policymakers to focus on stronger action, leading to solutions to tackle human-induced carbon emissions driving climate change in Paris. At the same time, the religious perspectives highlight the social values these choices represent, and how fundamental they are to our way of life. Statements Analyzed: Religious statements: Pope Francis’ Encyclical (http://tinyurl.com/ptcm9bz), A Buddhist Declaration on Climate Change (http://tinyurl.com/p9ge6xj), Islamic Climate Declaration (http://tinyurl.com/nqg98o7), A Rabbinic Letter on the Climate Crisis (http://tinyurl.com/qcyzmqg). Scientific statements: Earth Statement (http://tinyurl.com/nqw7d9b), Our Common Future under Climate Change (http://tinyurl.com/q5oy4x5), Planet under Pressure (http://tinyurl.com/7mvc9vq) Business statements: Institutional Investment Group on Climate Change (http://tinyurl.com/oaf6ooz), The World Bank: Putting a Price on Carbon (http://tinyurl.com/nrkagpx). NGO statement: Paris 2015: getting a global agreement on climate change (http://tinyurl.com/mhbqt2r). National leaders: Leaders’ Declaration G7 Summit 2015 (http://tinyurl.com/nmuagfd) This post summarizes research by Marius Sandvoll Weschke and Kimberly Nicholas presented at the Transformations conference held in Stockholm, October 2015.

Read an interview with Marius about this work in the Finnish newspaper Kyrkpressen here. Here are some tips I compiled with my friend and colleague Josh Goldstein when we were both finishing our PhDs and tackling the job market. Good luck, job seekers!

Here are some of my top tips, and a suggested template of a letter to contact a potential advisor at the end:

I came across your work through X (conference/paper/my professor X’s recommendation). I am very interested in your approach to (topic) using (method/specific thing they do that interests you). I’m writing to inquire if you are accepting PhD students in your lab for fall 2016? I am aiming to pursue a PhD dissertation focusing on X topic, specifically looking at the question of X puzzle in X case for X purpose. My background is in X bachelors from X university/Y masters from Y university. My research to date has focused on X, which I investigated most recently in my master’s thesis on X topic in X place, finding that X key highlight (please see attached thesis FYI). I have written about this work in a popular science blog here (link) and am currently preparing the manuscript for submission to the journal of X with my supervisor X. I also have experience in X business/NGO/policy/government, where I accomplished X. For more details, please see my attached CV. Regarding funding, I am currently applying for funding from X, X and X scholarship agencies to support the project I’ve outlined above. If there are any additional funding sources that you think might be a good fit to support this work, I would really appreciate any tips. And of course, if you have any currently funded projects that could support a PhD student, I would love to hear about them. Thank you very much for your time and I look forward to hearing from you. Best regards, You ---- If you don’t hear back from them in 2 weeks, resend your message with a polite note at the top: “Dear Dr. X, I thought my earlier message may have caught you at a busy time. I’m still very keen to pursue a PhD in your lab, and hoping you can let me know if you are accepting new students next fall. Thank you, X” If there’s someone you’re really excited about who hasn’t gotten back to you, consider picking up the phone to call them. Bold move, but it just might work! People get a bajillion emails, but few phone calls nowadays. Practice a shortened version of the text above to ask them. It’s smart to apply to at least several schools (I just checked and I applied to seven PhD programs, which now seems excessive- but at least three is good). You don’t know where you’ll get in, and you’ll have to consider personal factors about where you want to live, so it’s good to have options. Most advisors will be contacted by many students and will have many applicants for each open position in their lab. So, you both are on the lookout for the person who will be the best fit! Most advisors will understand this (some may even ask where else you are applying). That said, if you apply for external fellowships, you may have to specify your top choice for where you want to go and who you want to work with (depending on the fellowship). In this case, it’s important to share your plans with your potential advisor and get their agreement to support your application. In any case, if you really click with a potential advisor, consider asking them to give you feedback on your external fellowship application (for something like NSF GRFP, not for their own university applications where they would have a conflict of interest). Hopefully their comments can help you strengthen your proposal. In any case, good communication with a potential advisor is important, so ask them questions to clarify expectations or any points of confusion. Hope this helps- let me know if you have any comments! I’m on the train home to Lund, Sweden, returning from last week’s gathering of 2,000 climate change scientists from 100 countries at the Our Common Future Under Climate Change conference in Paris. The meeting was the largest gathering of scientists in advance of the United Nations talks that will also take place in Paris starting November 30th, where the next round of an international climate deal will be negotiated.

The meeting summarized the state of the science, and looked ahead for the role science could play in the months leading to Paris, and beyond. I’m using this time speeding past German wheat fields and over sparkling Danish lakes to reflect on my impressions of the conference. My summary of the key messages: the risks of unchecked climate change are increasingly scary, prompting scientists to turn towards a focus on preparing for the inevitable risks while calling for fundamental changes to our energy systems to avoid the worst impacts. I see it as a time of reckoning for the scientific community: this pivot towards focusing on solutions recognizes the increasingly unavoidable ethical dimensions of studying such a huge threat. Are you a UNFCCC negotiator or IPCC author? Skip this section. Otherwise, here's the deal: In 2009, 141 nations agreed in principle to limit climate warming to 2°C (3.8°F) above pre-industrial temperatures, in line with an international agreement made in 1992 to avoid “dangerous anthropogenic [human-caused] interference” with the climate system that could threaten food production and ecosystems. The 2° target has been criticized, but it’s clear that the risks of climate change increase with greater temperatures. (Read more on climate diplomacy here from Brad Plumer at vox.com.) We have already used up almost half (0.8°C) of this 2° allocation, and at current emission rates, we are on pace to warm up to nearly 5°C (9°F) by the end of the century. Five degrees may not sound like much, but when the Earth was last 5°C colder (about 20,000 years ago, due to natural variations in its orbit around the sun), Chicago would have been buried beneath an ice sheet more than twice as tall as the Sears Tower. For nature, for cities, and for people: five degrees is a huge difference, and a five degree warmer world would be largely unrecognizable to us. Thus the focus on bending the path we’re on to limit the amount of future warming that occurs, while also aiming to meet other goals like eliminating poverty. It’s warming, it’s us, we’re sure… now what? Although the notion that the Earth is warming and this warming is caused by human activities sometimes still appears to be contested in the media, after decades of accumulation of overwhelming evidence and analysis, there is really no scientific debate about this. Therefore the discussion at this scientific conference focused on two areas: the “problem space” of the risks posed by continued climate change, and the “solution space” of opportunities to address and lessen these risks. News flash: Climate change is bad Even for an audience who works with climate change data every day, there were some stark reminders of how serious the problem is. Over the past years, as evidence accumulates, scientists have progressively revised their estimates of how likely dangerous risks like extreme weather events or major ice sheet collapse are. I attended one session that traced this history, showing that, in the latest report, a new color scheme had to be introduced to capture “very high” risk of some of these serious reasons for concern under warming of more than 2°C. That means- the risks of climate change are worse than we thought. It’s not just future projections – the effects of climate change can already be seen today. Camille Parmesan of Plymouth University showed that across continents and ecosystems, half the species studied have already changed where they live, and two-thirds changed when they live (for example, flowers blooming earlier in a warmer spring) to track changing climate. This large response to the relatively small changes in temperature we’ve seen today is worrying for the future. Paul Leadley of the Université de Paris-Sud argued that our common future should recognize the value of the many species with whom we shared the planet, whose options under climate change are limited to “move, adapt, or die.” Clearly, the path we are on is a bad one. It’s no surprise, then, that much of the meeting focused on what we should do about changing it. Manage changes we can’t avoid, and avoid changes we can’t manage Historically, the relationship between limiting climate change (mitigation) and dealing with its impacts (adaptation) has been a contentious one, with concerns that a focus on dealing with the effects of warming could decrease motivation to limit the warming that occurs. (This is a bit like a patient who thinks he can keep up a sedentary lifestyle fueled by unhealthy foods as long as he takes blood pressure medication, rather than making lifestyle changes to eat better and exercise more to prevent high blood pressure in the first place.) However, a more unified voice emerged from this conference, noting both the need for strengthening our capacity to adapt to climate change, and the limits that we face in managing risks under increasing warming. In daringly PowerPoint-free reflections, Saleemul Huq of the International Center for Climate Change and Development noted that adaptation is not just dealing with risks, but taking opportunities to be better off and to make transformational changes. He cited the example of sending kids from areas facing saltwater intrusion in his native Bangladesh to school to give them opportunities other than farming. However, he also cautioned that some people face big risks under even the low range of warming, and it’s very doubtful that adaptation can be a sufficient solution in a +3 or +4°C world, sharpening the need for mitigation. “The age of carbon is over” The ultimate conclusion of the conference, summarized by Scientific Committee Chair Chris Field at the closing plenary, was that “We are moving to a post-carbon era, where climate change mitigation and adaptation are combined with other goals to build a sustainable future.” Why a “post-carbon” era? Recent analyses have concluded that we have a limited amount of carbon we can release to the atmosphere in order to hold warming to 2°C or less (the so-called carbon budget). If we emit more than this, we risk experiencing higher warming, where risks become more severe and less manageable. Previous research has shown that, to meet a 2° target, the majority of fossil fuel reserves including 80% of coal and half of gas reserves should remain unused. At the conference, Chris Field noted, “We’ve never said, let’s cut down the very last tree, let’s catch the last fish in the ocean. Why should we burn the very last carbon?” The conference Outcome Statement reaffirmed that our carbon budget, the amount we can emit from here to eternity, is only about 20 years’ worth of current emissions. Further, because of the long lifetime of greenhouse gas warming pollution in the atmosphere, to achieve a stable climate, carbon emissions must eventually go to zero. (This means "decarbonizing"- using clean energy to get the services we want, like hot showers and cold beers, without the carbon pollution to the atmosphere that inevitably accompanies burning fossil fuels to deliver them.) Hans Joachim Schellnhuber of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research expressed this same view more bluntly: he sounded a clarion call that “the age of carbon is over.” He warned that "it is a very bad idea to go beyond two degrees” and suggested: “Let's take this as the reference line, what are we going to do about it?” He said that if there is any chance of avoiding dangerous climate change, an "induced implosion of the carbon economy” is needed. Society’s response to climate change Indeed, there was converging agreement from scientists, political leaders, and journalists at the conference that fundamental changes are needed to achieve a zero-carbon society, not just incremental improvements at the margins. Several high-level French politicians and diplomats at the meeting were blunt about the urgency of tackling climate change. French Research and Education Minister Najat Vallaud-Belkacem issued a stark warning, saying that "unless we have widespread climate action, we will be the generation that knew what had to be done, but didn't do it." Segolène Royal, French Minister for the Environment, Energy and Sustainable Development, echoed the same message, calling on scientists to speak with a clear voice in the run-up to the Paris climate change negotiations in December. "We have won the battle of ideas, now we must win the battle for action," she said. The conference featured a packed lunchtime session on one approach for changing course that’s rapidly gaining traction: the fossil fuel divestment campaign. Scientists came to hear Damian Carrington, Head of Environment at The Guardian newspaper, describe the paper’s #keepitintheground campaign, which he said was "rooted in the reality that there’s far more carbon locked in the ground than we can safely burn.” Several speakers including Karen O’Brien emphasized that if we act swiftly and boldly we have the technical capacity to meet the 2° target. Nobel laureate Joseph Stieglitz pointed out that this action could present economic opportunities. A key question now seems to be: how do we get there? Pivoting from problems to solutions Many scientists seem to have decided to dedicate themselves to answering this question. This is part of a larger shift in the scientific community that I saw throughout the conference, articulated by Chris Field in the closing plenary as a “pivot” from problems to solutions. He described the scientific community shifting its focus from describing the climate change problem, to exploring and evaluating solutions to decrease the amount of warming that occurs, and prepare for the warming that cannot be avoided. As part of envisioning and exploring solutions, as well as motivating action, several speakers talked about the need for scientists to help create a positive vision of a better future. In particular, Ken Caldeira of the Carnegie Institution for Science raised the need to highlight the attractive elements of a low-carbon future, to imagine the world we’d like to create: full of healthy, happy, prosperous people. Jeffrey Hardy, an energy regulator from the UK, echoed this need, pointing out that there could be something for everyone in a low-carbon future, whether it was smart technology or better communities or clean air for everyone. Even without considering the added benefits of addressing climate change, he concluded: “Don’t we want to live there anyway?” There was a bright spot for hope that social and political change can be possible, and sometimes more rapid than scientists predict. A story shared by Diana Ürge-Vorsatz offered a potential lesson for the climate negotiations this fall, where ambitious goals spurred change much faster than expected: “When we wrote about zero-energy buildings less than a decade ago, most researchers didn’t think it was possible. Today it’s in European law. The law came out before the scientific community was convinced it was feasible. The regulations pushed the industry to innovate, and it’s having a very significant impact. Really, a miracle happened.” The human challenge of climate change Finally, I saw a welcome expansion at the conference beyond a focus on technical challenges of climate change to address underlying ethics. I see this as a sign that scientists are examining their role in society more closely, and trying to find ways to make their contribution meaningful. For example, Karen O’Brien pointed out that addressing climate change forces us to ask what risks we can accept or tolerate, which is a question of beliefs and values. Chris Field outlined a new role for science in bringing objective analyses to the table to inform ethical debates. He emphasized the human questions raised by climate change, forcing us to articulate and perhaps change “how we think about the interests of the poor versus the rich, the future versus the present, and nature versus economies.” This kind of thinking is a fundamental transformation indeed, one that will carry on well beyond the next few months on the road to Paris. Studying climate change offers us the chance both to push the frontiers of scientific knowledge, and to delve deeply into human nature. As a researcher, I have studied the impacts of climate change on crop yields and quality. My findings, along with the mass of evidence accumulated by hundreds of my colleagues, worry me that we are eroding our ability to feed ourselves- one clear reason in my mind to urgently reduce climate change. But it’s clear that research findings alone are not sufficient to change policies and agreements- much less hearts and minds. Faced with the stark realities of climate risks, as well as cautious optimism that change is possible, I left the meeting wondering how the response to climate change will unfold this fall and beyond. I will be back in Paris in December to watch one pivotal moment where the nations of the world will express their values, in ways that will be seen and felt for decades to come. When I think about Our Common Future, it is my hope that it is one that will reflect the best of human nature. This post draws on daily newsletter updates that Johannes Mengel of the International Council for Science and I wrote during the Our Common Future Under Climate Change conference, and benefitted from his helpful editing. The original newsletters can be read here: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, Day 4, and the Wrap-Up. I've just returned from a field trip to Lake Bolmen with 50 international high school students from Helsingborg. The lake is the source of Lund's drinking water (which is piped 82 kilometers to Lake Ringsjön!). The workshop was led by my colleague Ann Åkerman, in collaboration with the local water agency, Sydvatten, to promote youth water awareness and to help educate the next generation of potential water managers in Sweden.

The students camped out and learned outdoor skills like edible plant identification and water filtration methods from local guides and teachers from the local vildmarksgymnasiet (wilderness high school)- a type of Swedish school that combines usual academic lessons with practical outdoor skills in hunting, camping, fishing, and backcountry guiding. Ann and her colleague Anna-Karin from Sydvatten ran a role-play activity on water management, my colleague Torsten Krause led a workshop on conflicts over water in Sweden and California, and I led an exercise on virtual water. We traced the water needed to grow our food, for example showing that a simple margarita (cheese and tomato) pizza requires enough water for more than 20 showers. I also asked the students to test out and give me feedback on some quizzes and worksheets that my master's student, Seth Wynes, has developed as part of his LUMES thesis on high-impact actions for high school students to reduce their carbon footprint. In the quiz, only one group correctly identified that avoiding flying was a more effective way to reduce their carbon footprint than upgrading light bulbs. (In fact, Seth's research has shown that avoiding one long-haul flight saves more than 10 times more carbon than upgrading light bulbs, and yet the Canadian high school science textbooks he's analyzed suggest light bulbs as a climate solution more than five times as often as they mention air travel). I hope we can incorporate these teaching materials in local high schools here in Sweden, as well as the Canadian schools where Seth is working to implement them. It's thesis season! Our LUMES master's students are turning in their last six months of academic blood, sweat and tears (AKA, their theses) in nine short days.

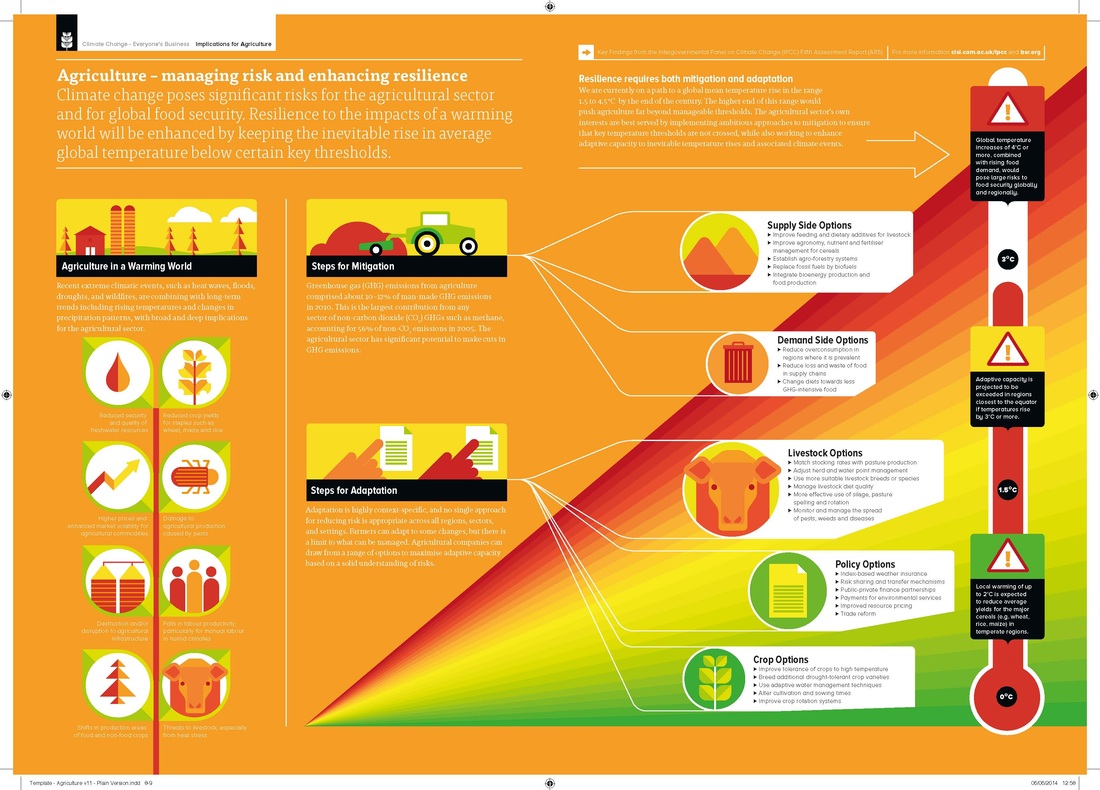

Just in time- here's a checklist I've developed to help students give appropriate credit to their original sources. This is one of the most common problem areas I see in student writing. Following this checklist will help you contribute to scholarly conversation and avoid problems from unclear citations. This checklist aims to serve several purposes: 1. Demonstrate appropriate research ethics in fairly crediting ideas to their original authors. 2. Give more credibility to your research by grounding it in established literature, and showing where you have added new knowledge. 3. Help your reader follow your logic and understand your main claim, based on the evidence that supports it. 4. Follow a well-established format for citation (APA style), to help readers find and understand the sources you have used and the way in which you've used them. 5. Avoid plagiarism (which is every student's responsibility to avoid- even unintentional plagiarism can carry a penalty of up to six months' suspension at Lund University). Comments or corrections welcome. Happy revising! I was recently contacted by a Swedish high school student writing a senior thesis with some questions about climate change and food production. Here are their questions, and my answers. 1. What effect does global warming have on food production? What kind of impact does this effect have on rich and poor countries? In general for most major food crops, increasing temperatures decrease yields. The more warming, the greater yield loss. About 2/3 of food that people eat worldwide (measured in calorie production) comes from 4 crops: wheat, maize, rice, and soybean. These crops are sensitive to temperature, as you can see below. Here rice is not so much affected (the green line does not decline very much with warming), and soybean can also tolerate some higher temperatures (the blue line does not drop much until more than 2° of warming occurs), but wheat (purple line) and maize (called corn in the US; red and orange lines) start to experience big yield losses that increase with more warming. The effect of warming on crops depends on physics (how much does the atmosphere warm) and biology (how do crops respond to warming), as well as social systems (how well can people cope with change and what resources do they have to do so- this can include traditional knowledge as well as technology like irrigation). Even rich countries can be affected. For example, I have just published a paper with colleagues that shows that wheat yields in Australia are likely to decline 50-70% with high warming from continued heat-trapping pollutants (greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide). 2. What actions/solutions are there to make the impact as little as possible? What have the countries done so far to prevent this? There are many ways to reduce climate change, for individuals, organizations like schools, communities, businesses, and countries. Individuals can consider their carbon footprint. Some of the biggest ways to reduce this are to eat less meat or adopt a vegetarian diet, minimize travel especially air travel, and choose to have fewer children. Organizations can assess their resource use and find ways to focus on delivering the desired services (like education) with less resource inputs. Fundamentally, to reduce the risks of climate change, the world needs to move towards a goal of zero carbon emissions. This means we need to stop burning fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas, which contain a lot of carbon that turns into the heat-trapping pollutant carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. How we use land to grow food is also a major contributor. Your question about what countries are doing is very timely. The international process around climate change is coordinated by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. There will be a meeting in Paris (called COP21) starting in November where new treaties are negotiated. Many countries have made good progress. One example that got recent attention was the deal between the US and China, which you can read about here. However, much more work needs to be done to meet the targets for limiting climate change to 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Right now, the countries are making statements about what their commitments will be to reduce emissions. You can read more here for an overview, and here for Europe. 3. Are there countries that can have a positive impact due to global warming? Yes, some areas and some sectors are likely to benefit from climate change. For example, it may be possible to grow more crops in Canada and Russia and other northern areas if they have longer growing seasons and warmer temperatures. Melting of Arctic ice could open up new shipping routes. However, the overall impacts of climate change are negative, and they outweigh the benefits. Many studies have shown that it will be cheaper to avoid climate change, than to spend money to adapt to change, especially if we continue high emissions and therefore experience a lot of warming, which will produce a lot of changes in the environment that are expensive and difficult or in some cases impossible to adapt to. 4. Are there any plans for the future? How will it look in the future when certain crops are lost or run out? The way I think about dealing with climate change is to “manage what we can’t avoid, and avoid what we can’t manage.” There are many options to deal with climate change in agriculture, like changing planting dates of crops, switching varieties, or using more irrigation. However, the more warming we experience, the more difficult it is to adapt, as the infographic from the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership briefing on the latest scientific studies from the shows. This is why it’s so critical to limit the amount of climate change we experience by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, so that the impacts are manageable.  Credit: Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, IPCC Climate Science Business Briefings, "Agriculture" infographic, 2014. There are 13 excellent visual summaries of the latest climate science here: http://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/business-action/low-carbon-transformation/ipcc-briefings/agriculture |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2023

|

KIM NICHOLAS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed